Despite 2024 being a momentous year for UK coal mining and use, the fight's not over.

The UK steel and cement sectors (and to a lesser extent, bricks) are the largest users of coal following the closing down of the UK's last coal-fired power station in September 2024. But tried and tested alternatives to coal exist. Check out our coal dashboard for our most recent coal stats including an industry break-down. We support the UK Government's commitment to ban new coal mines opening in the UK - but this must be accompanied by a commitment to rapidly wean domestic industry off coal by adopting existing alternatives. Failing to do this simply off-shores the dangers and localised environmental harm of coal mining to where it's out of sight. This kind of practice marked the British colonial period, where some of the dirtiest and most grueling work was forced upon colonised countries, to supply and develop the UK. Continuing this pattern is called 'neo-colonialism', and the UK must avoid this by de-coaling domestic industry.

As the UK no longer produces thermal coal, the type used by the cement industry (and to a lesser extent in the steel industry), 1.78 million tonnes was imported in 2024 – primarily from Colombia and South Africa, two countries plagued with poor track records in coal mine-based health and safety, forced displacements of communities, and killings of environmental defenders. Without a plan to decisively and rapidly wean cement works off coal, the UK is open to accusations of perpetuating neocolonial patterns of trade.

Carbon footprint

The steel industry produces 9-11% of the annual CO2 emitted globally, contributing significantly to climate change. In 2024, on average, every tonne of steel produced led to the emission of 2.2 tonnes of CO2e (scope 1, 2, and 3). Globally in 2024, 1,886 million tonnes (Mt) of steel were produced, emitting in the order of 4.1 billion tonnes CO2e (75% of which are direct emissions). This is largely due to the reliance on ‘coking’ coal in blast furnace primary steel production.

Coal-free steel pathways

Four of the five biggest global steel producers aim to reach carbon neutral steel production by 2050. This would be through a combination of using ‘electric arc furnaces’ (EAF) to recycle scrap steel into secondary steel products, and a newer technology called Direct Reduced Iron that replaces coal with natural gas or hydrogen in primary steel making. The hydrogen option could be generated from renewables but relies on the roll-out of much more renewable generation capacity and massive green hydrogen infrastructure, which has so far received little of the huge investment required. So where this new Direct Reduced Iron technology (also requiring significant investment) is being used, it’s generally with natural gas instead. Those steelworks could be switched to hydrogen in the future, if the price of green hydrogen drops to a competitive level and the infrastructure to get the hydrogen to steelworks is built.

Threats to coal-free steel decarbonisation

There is a global over-supply of steel, primarily generated by China which produced 54% of global output in 2023. This has reduced the price that steel can be sold for to the point that many steelworks are running at a loss, supported by government subsidies to continue operating. This threatens the very significant private sector investments needed into green steel production as the industry’s current position makes a profitable return on that investment unlikely. A blast furnace can continue for 15-20 years before undergoing a ‘relining’ (refurbishment) process to extend its life further. Relining can cost 25-50% of the cost of a new blast furnace, but still amount to hundreds of £millions. Due to the long life and large capital investments, it’s essential that investments now are in greener steel-making processes or the world will be ‘locked in’ to CO2-intensive steel-making for many years to come.

In 2024, UK steel production made up 32% of domestic consumption and was responsible for 13.4% of GHGs from manufacturing, and 2.2% of total UK greenhouse gas emissions. The vast majority of this footprint is due to the coal burned at Scunthorpe steelworks. With the UK Government rightly ruling out any new coal mining projects in the UK, it is vital that UK steelworks becomes coal-free. Switching domestic coal mining for coal mining abroad would perpetuate colonial patterns of trade where the impacts of extractive industries are off-shored.

UK primary steel-making is wholly dependent on imports for the two main resources needed to make steel: ‘coked’ coal and iron ore. Coal needs to be ‘cooked’ in ‘coking ovens’ before it becomes coked coal capable of burning at very high temperatures required in blast furnaces. The UK closed its last coking oven in Port Talbot in March 2024. Since then, UK primary steel-making has depended on other countries to process coal in coking ovens before being imported into the UK.

The UK’s largest steelworks, Tata Steel UK’s Port Talbot steelworks, recently closed its blast furnaces, which had come to the end of their operational life. With £500 million from the UK Government, Tata seized the opportunity to shift from making coal-based blast furnace primary steel to using electricity to recycle scrap steel into new secondary steel products instead.This technology is called an ‘electric arc furnace’ (EAF). Although the transition should have had more Union and worker involvement, the conversion to EAF is a pragmatic move given the UK’s scrap steel surplus, the financial losses being made in the blast furnace steel production, and the UK’s net-zero commitments. Four of the UK’s other steelworks also recycle scrap steel using EAFs. The fifth is British Steel’s Scunthorpe steelworks, which still produces coal-based primary steel, and so is the second biggest single site source of CO2 in the UK.

Scunthorpe’s blast furnace steelworks needs to decarbonise to remain competitive, improve local air quality, and avoid fuelling climate chaos. Before the UK Government took partial control of the steelworks around April 2025, the operators – Jingye Group – claimed financial losses of £700,000 per day. Additionally, customers – who will soon face mandatory carbon reporting – may increasingly choose to import lower carbon steel from other European countries like Sweden and Spain who are pursuing low-emission primary steel production. The current options for Scunthorpe steelworks are:

1) convert to Direct-Reduction Iron technology to produce primary steel

2) convert to recycling scrap steel in a EAF to produce secondary steel products.

Producing secondary steel option would be much cheaper, but politically difficult as it would mean the loss of many jobs and the loss of the UK’s primary steel-making capacity. Find out more about the technology options below:

Read more about coal in steel in our 2021 report.

Blast furnace primary steel production: Metallurgical-grade coals converted to ‘coke’ which has a dual role in a blast-furnace, providing the required heat and creating a chemical reaction with iron ore reducing it to ‘pig’ iron which is heated with other additives (including small quantities of existing scrap steel) to make steel.

Electric arc furnace secondary steel production uses 99% less coal than blast furnaces per tonne of steel produced by using electricity to melt down scrap steel to make secondary steel products, with small quantities of coal added to remove certain impurities. In countries, such as the UK, which generates a large share of its electricity through renewables, EAFs have a much smaller carbon footprint than blast furnace steel production. The UK currently produces a surplus of scrap steel, exporting it to EAFs abroad. Having greater EAF capacity in the UK will keep the scrap here, and the jobs it supports. Steel is – in theory – an endlessly recyclable product, but when it’s fused with other metals and materials, or has other properties added to it, it can be challenging to recycle it in EAFs into high-grade metals needed for certain applications, even with small quantities of coal added to remove certain impurities.

Direct reduced iron (DRI) primary steel production: is an emerging alternative to blast furnaces where natural gas or hydrogen replaces the role of coal in heating and reducing high-grade iron ore down to iron, ready for primary steel-making in an electric arc furnace. There are successful commercial test-cases for this technology, such as HyBrit in Sweden which uses hydro-generated green hydrogen to make steel. However, green hydrogen is prohibitively expensive, currently, so DRI facilities tend to use natural gas whilst being “hydrogen ready”. DRI production also makes capture rates for CCS much higher than a blast furnace.

It is vital that the forthcoming UK Government’s green public procurement policy for construction and Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism should be sufficiently robust so as to support UK low-emission steel to compete with cheaper higher emission steel imports. Together, this should add confidence within the British steel sector that the UK Government’s public procurement pipeline will be a pipeline that supports domestic industry.

The UK Government must take action to secure the UK’s production of virtually coal-free secondary steel-making:

The UK Government’s steel safeguard Tariff Rate Quota expires in June 2026 – but the UK’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism is not expected to be implemented until 2027. The UK Government should introduce stop-gap measures to prevent high-carbon steel imports causing carbon-leaking and undermining investment to produce greener steel in the UK.

The UK Government should engage in honest conversations now with unions and workers at the loss-making Scunthorpe Steel Works regarding the future of steel-making at the site. EAFs are currently the only financially viable technology to replace the coal-fed blast furnaces currently in operation. That would result in job losses but this can be a just transition with enough time to allow for proper planning, union and worker involvement, and funding. This should be followed with a commitment to add DRI primary steel production by mid-2035 as the technology and green hydrogen are expected to become more financially viable.

Worldwide, the amount of cement being used for every person in the world has nearly tripled in the past 45 years and demand is projected to increase over 33% by 2050. This demand is driving an exponential growth in cement production - and 'clinker', a key binding agent that averages around 75% of cement (but can make up to 95% of the content of Ordinary Portland Cement). To make clinker, limestone and clay are heated to around 1450c, creating a chemical reaction that forms ‘clinker’. To generate this heat, the industry generally burns fossil fuels - although alternatives exist. Burning the fuel emits an average of 33% of the clinker CO2 footprint, with the remainder (67%) emitted by the chemical reaction of the heated limestone. Clinker is responsible for 94% of the total CO2 footprint of cement. In total, the cement industry has reduced its reliance on fossil fuels to heat clinker by 22% from 98% in 1990 to 76% in 2023, with post-use mixed waste and biomass increasing their share as alternative fuels. This concrete progress has helped reduce the carbon intensity of the fuel mix by 8% between 1990 and 2023. Unfortunately, this reduction has been outstripped by increases in cement production overall since 1990, so total fossil fuel consumption has actually increased by 100 million gigajoules (GJ), from 1.78bn GJ in 1990 to 1.88bn GJ in 2023.

(Except where specified, figures are sourced from the GCCA, Getting the Numbers Right Project, Emissions Report 2023 - for External Stakeholders industry-reported dataset)

Cementing coal use

Today, 49% of the heat needed to make clinker is generated by burning coal. Consequently, the cement industry consumes around 4% of global coal produced, which amounts to approximately 330 million tonnes of coal per year. UK Government research and commercial examples from around the world indicate that the elimination of fossil fuels in cement production is possible. Thermal coal is the most common fuel burned to produce the high heat required.

Successful, at-scale, examples already exist of cement works burning 100% fuel alternatives to traditional fossil fuels, including pilot projects using combinations of hydrogen and biomass (UK) and hydrogen and electricity (Sweden). Yet, innovations such as use of hydrogen and kiln electrification are forecast to play only a small role, providing 10% of energy needs by 2050. Worldwide, only 24% of cement in 2023 was produced using alternative fuels, with 76% of cement produced using fossil fuels (37% of cement overall is heated using coal). The continuing reliance on burning fossil fuels to generate heat at cement works contributes to its high CO2 footprint – particularly its upstream footprint due to the resources and methane emissions associated with mining coal. Globally, the cement industry is responsible for up to 8% of CO2 emissions (but only 1.5% of UK CO2 emissions) – nearly as much as steel.

Coal-free fuel examples from around the world:

Holcim’s cement works in Saint-Pierre-la-Cour, France, uses a combination of calcined clay to reduce clinker content required in the cement, and biofuels and waste heat recovery systems to heat the remaining clinker required. This combination has displaced 100% of fossil fuels from its calcined clay cement production process to deliver up to 500,000 tonnes a year. This cement works received funding from France’s ‘France Relance’ industrial decarbonisation fund.

Holcim’s cement works in Retznei, Austria, used alternative fuel in 96% of its fuel mix last year – virtually eradicating fossil fuels from its operations – and is working towards 100%.

JK Cement’s cement works in Muddapur, Karnataka, India, has increased its use of alternative fuels to 78%, and is completing the installation of a waste heat recovery system, which it expects to make the cement works 100% fossil fuel-free.

Huaxin, a global cement producer headquartered in Wuhan, China, has reached 40% and 60% alternative fuels (mainly refuse-derived fuels) at its Diwei Chongqing (2,500 tonne/day) and Huangshi cement works, respectively. In developing economies, certain alternative fuels are highly variable in materials and moister content, resulting in heating fluctuations that challenges consistent quality in clinker production. At Huangshi cement works, Huaxin uses AI and other technologies to adjust production processes in real-time response to changing fuel properties, allowing it to create consistent clinker quality.

Globally, the clinker ratio to cement (Portland and blended) has reduced from 78% in 2012 to 75% in 2023. The use of clinker substitutes has correspondingly increased by 12.7 million tonnes between 1990 and 2023, but much of this increase may be accounted for by the overall growth in cement production. Although most ‘green cement’ works around the world substitute up to 40% of clinker, there is at least one commercial example of a cement works substituting up to 100% of the clinker in their cement production. The use of alternative cementious materials reduce, or even eliminate the needs for clinker. Unlike clinker, these alternative cementious materials don’t require as much, or any, heating – thereby reducing the amount of coal burned. Some of these materials, such as the coal by-products of fly-ash and blast furnace slag, are in increasingly short supply as economies decarbonise. However, other clinker substitutes such as burnt rice husks do not face supply issues, and a lack of acceptance by the construction sector continues to be the most limiting factor in producing more cement with a lower clinker content. One solution to this would be Government mandating that publicly-funded construction projects must use entirely or partially ‘low carbon’ cement products where clinker substitutes have been included.

Clinker substitution examples from around the world:

Hoffmann Green cement works in Bournezeau, France, has a capacity to produce 50,000 tonnes of three varieties of cement per year, all with 0% clinker content. This cement works replaces clinker with a mix of slag, clay, gypsum – supplied by local producers. It also removes the need for further extraction, unlike clinker which requires quarrying limestone. This cement works received funding from France’s ‘France Relance’ industrial decarbonisation fund.

US start-up, Sublime Systems has developed a new 0% clinker cement using calcium silicates and other commonly used substitutes in an electrochemical reactor, which requires heating only to 100c. Its pilot cement works only has capacity to produce a few hundred tonnes of cement per year, but it is developing a new cement works with capacity for up to 25,000 tonnes per year by 2026.

CRH’s Jura cement works in Wildegg, Switzerland, uses calcined clay to produce a cement with a clinker factor lower than 65%, with potential for further reductions. One tonne of calcined clay replaces on average 0.75 tonne of clinker, thereby saving more than 0.25 tonne of CO2. The resulting cement contains approximately 20% less CO2 per m3 compared to ordinary Portland cement.

In contrast to worldwide trends, UK cement production has been in decline since a peak in the 1970s, and roughly halving since 1990. Despite this decline, the UK cement industry still burned just under 400,000* tonnes of coal to make 7.3 million tonnes of cement in 2024 – averaging roughly 1 tonne of coal for every 18 tonnes of cement. To put that into context, around 8,000 tonnes of cement is needed for a new hospital, while between 3-5 tonnes are needed to build a four-bedroom family house.

*There is no cement-specific coal consumption statistics available, but the UK Government reported that 395,000 tonnes of coal were used in the minerals industry in 2024, the vast majority of which would be cement. The burning of this coal emitted around 1.24 million tonnes of CO2 in 2024, based on industry reported emissions (33% of CO2 emissions released from coal and limetone which totalled 3.8 million tonnes of CO2).

At the moment, there are isolated examples of cement works around the world that operate entirely without burning coal or fossil fuels. Yet all large UK cement works continue relying on coal and fossil fuels. The £3.2 million public fund to research pathways to decarbonise UK cement making is welcome, but to get value for money, proven pathways must be implemented at commercial cement works.

Carbon Capture & Storage - risks:

There is also a proposal to create a CCS network (Peak Valley Cluster), funded in part by the new UK National Wealth Fund. The CCS project would aim to reduce CO2 emissions from several cement works in Derbyshire and Staffordshire. But the high-risk CCS technology is an extremely expensive decarbonisation pathway, with high construction and running costs. The UK Government pledged an eye-watering £22 billion from 2025, driving even more households into fuel poverty (currently 11% of UK households struggle in energy poverty). Given the many £billions poured into the technology around the world, it has a disastrous global track-record of cancellations, suspensions soon after operating, and under-performance of up to 50%. Crucially, CCS will also do nothing to remove coal from the cement-making process, failing to reduce any upstream emissions or harms associated with coal mining and resource extraction in the supply chain. Investment in CCS is investment diverted from eliminating our use of fossil fuels, thereby prolonging our reliance on them.

Although the UK entirely removed coal from its electricity generation with the closure for Ratcliffe Power Station in October 2024, it continues to rely on coal in a number of industries. The UK must rapidly decarbonise these carbon-intensive industries to meet its climate commitments. Click on the tabs below to find out about each industrial application of coal.

WORLDWIDE

WORLDWIDE

The direct use of coal as a feedstock (not just energy) is particularly significant in China, where coal is used extensively in coal to gasification plants to produce chemicals such as methanol, ammonia, and polyvinyl chloride (PVC). In 2017, China's chemical industry alone used about 180 million tonnes of coal as feedstock, which constituted about 5% of China’s total coal use that year.

China is unique in its heavy reliance on coal for chemical manufacturing, accounting for a large share of global coal-to-chemicals production. For example, 89% of methanol and 76% of ammonia production in China is coal-based, and producing 1 tonne of methanol from coal requires about 2.7–3 tonnes of coal.

India is also expanding its coal gasification capacity, with government plans to gasify 100 million tonnes (MT) of coal annually by 2030

In contrast, other major chemical-producing regions (Europe, North America, Middle East) primarily use natural gas or crude oil as feedstocks rather than coal.

UK

There is negligible or close to zero coal gasification industry in the UK as of 2025: over the past 20 years, gasification projects have focused on waste or biomass, rather than coal.

![]()

WORLDWIDE

Global brick production was estimated at 2.18 billion tonnes in 2020, resulting in approximately 500 million tonnes of CO2e (1% of current global GHG emissions). Brick production could rise to 3.35 billion tonnes by 2050. Approximately 375 million tonnes of coal are used globally per year in brick production, mostly as fuel to heat kilns. Research indicates that coal is added to clay bricks at rates of 1–15% by weight of the clay mixture.

Switching from coal to alternative fuels, together with more efficient kilns, will lead to reduced CO2 emissions.

UK

Heating brick-firing ovens in the UK uses a mix of natural gas, electricity, coal and coke, diesel and LPG fuels. The primarily for use of coal in bricks, though is as an additive to colour it. According to coal mining company, Energybuild Ltd, UK brickworks consume approximately 70,000 tonnes per year of additives, which includes coal.

Annual tonnage of anthracite coal used by the UK brickmaking industry is not made public but the proportion used within the UK generally falls within the range of 1–5% of the brick mix by weight, depending on the desired product characteristics. This contributes to the high emissions released from the raw brick materials upon firing.

![]() WORLDWIDE

WORLDWIDE

Activated carbon is typically made from charcoal (wood) and is a common filtration medium in water treatment systems. It can be manufactured from other sources, with anthracite coal being a common source. Alternatives include nutshells. These sources are first processed into activated carbon through high-temperature treatment to create a porous structure suitable for adsorption

The global market for coal-based activated carbon was valued at approximately USD 4.44 billion in 2024, with demand driven by applications in air purification and water treatment.

Alternatives to the traditional sand/activated carbon dual medium to filter water include glass, garnet, magnetite, and other materials.

UK

The exact annual tonnage of anthracite coal used by the UK water filtration industry is not made public but it does use both domestically mined and imported coal.

WORLDWIDE

WORLDWIDE

The cement industry consumes around 4% of global coal production, which amounts to approximately 330 million tonnes per year. Most of this coal is combusted to generate the heat required to fire the kilns to about 1450c to create the chemical reaction that produces cement. Roughly 0.5 tonnes of coal are needed to produce 1 tonne of cement.

Coal in cement production is primarily used as a fuel to heat kilns, and the burnt coal ash can also serve as a minor feedstock into the clinker. Fly ash and blast furnace slag (both waste coal products) are used as a substitute for clinker in cement production, and can increase the concrete durability. By using substitutes for kiln-based ‘clinker’ in cement production, the cement industry can significantly reduce its carbon footprint. Post-consumer waste can also be used as an alternative fuel to reduce the coal used to heat the kilns, helping to decouple coal from the cement industry.

UK

Of the cement sold in the UK in 2024, 33% was imported. UK cement manufacture has begun switching from traditional fossil fuels such as coal and pet-coke to the use of waste, waste biomass and waste part- biomass fuels. These alternative fuels now account for 43 per cent of the fuel used (2020), replacing the equivalent of half a million tonnes of coal every year. This means 1.16 million tonnes of coal would be used if it weren’t for replacement fuels, and 660 thousand tonnes of coal is still used in UK cement manufacture.

UK carbon dioxide emissions from concrete and cement were 7.3 million tonnes in 2018; around 4.4 million tonnes of this was ‘process emissions’ from clinker production, 2.2 million tonnes from fuel combustion, and the remainder from electricity use and transport. Owing to decline in cement production and increases in efficiency, the sector's direct and indirect emissions are 53% lower than 1990. UK concrete and cement accounted for around 1.5% of UK carbon dioxide emissions in 2018. UK Government research and commercial examples from around the world indicates that the elimination of fossil fuels is possible with no negative impact on clinker quality, kiln stability or build-up issues.

![]() WORLDWIDE

WORLDWIDE

The steel industry produces 9-11% of the annual CO2 emitted globally, contributing significantly to climate change. This is largely due to the reliance on coking coal in primary steel production. 4 of the 5 biggest global steel producers aim to reach carbon neutral steel production by 2050, using green hydrogen instead of coal.

UK

Scunthorpe Steelworks still relies on coal-based steel production, and is the second biggest single site emitter of CO2 in the UK. Port Talbot steelworks recently closed to convert to using electricity to recycle scrap steel, decoupling it from coal inputs. The other two large steel producers – Liberty Steel and Celsa also recycle scrap steel in ‘electric arc furnaces’.

To keep up with global decarbonisation trends, Scunthorpe steelworks needs to decarbonise as well. If not, customers aiming to reach their own climate goals will likely choose to import lower carbon steel from other European countries like Sweden and Spain who are pursuing low-emissions steelmaking projects.

Read more about coal in steel in our 2021 report.

![]() Graphite is a naturally occuring substance used in everything from pencils to batteries. Anthracite is one of several suitable carbon-heavy materials that can be used to make artificial graphite. If anthracite is used to make artificial graphite, it must be heated to extreme temperatures of 1,000c for ‘baking’ and up to 4,000c for ‘calcination’ to remove impurities making up 8% of the anthracite. This stabilises the artificial graphite end product. The heating would release greenhouse gasses in a similar way to if it were burned for household heating.

Graphite is a naturally occuring substance used in everything from pencils to batteries. Anthracite is one of several suitable carbon-heavy materials that can be used to make artificial graphite. If anthracite is used to make artificial graphite, it must be heated to extreme temperatures of 1,000c for ‘baking’ and up to 4,000c for ‘calcination’ to remove impurities making up 8% of the anthracite. This stabilises the artificial graphite end product. The heating would release greenhouse gasses in a similar way to if it were burned for household heating.

This process can be avoided by using natural graphite and scrap graphite. The UK doesn’t manufacture any artificial graphite and UK demand is also relatively low: “UK is a small net importer of natural and synthetic graphite”.

Türkçe için bu web sayfasına bakın.

The small city of Ereğli nestles between tree covered mountains and Turkey’s Black Sea coast. The city is dominated by the Erdemir steelworks. It is one of three blast furnace steelworks in Turkey, using coal to produce steel. Erdemir is a mighty presence in the lives and lungs of the people living nearby.

Local people’s homes sit in an amphitheatre surrounding the vast steelworks, which sends plumes of steam into the air every few minutes that shimmers and obscures apartment blocks across the bay. Investigators from Coal Action Network travelled to Turkey to speak with people currently affected by Turkish coal burning facilities, like the Erdemir steelworks, when it looked possible that a new coal mine would open in Cumbria and supply coal to Turkey, perpetuating the local populations’ air pollution issues. For more information on why Coal Action Network visited Turkey and links to UK coal mining, see this page.

Turkey uses imported coal in its steelworks and power stations, as well as mining domestically.

Turkey is the 8th biggest steel producer globally. In 2023, it produced a massive 33.7 million tonnes of steel and consumed 21.1 million tonnes of scrap metal, according to World Steel Association. 27 of the 30 steelworks in the country produced steel by melting down scrap metal produced in Electric Arc Furnaces (EAF), producing 72% of the country’s steel output. There are three blast furnaces that use coal, converted into coke, in the steel making process, and many of the EAFs use coal to provide heat. This coal is largely imported. Russia supplies 73% of Turkey’s coal imports, and Colombia the bulk of the remainder.

EAFs consume large amounts of electricity. In Turkey, much of this electricity comes from coal through the power grid. One Turkish EAF has its own coal power station. Coal power supplied 35% of Turkey’s electricity in 2022. Turkey both imports and exports large quantities of steel (18 million tonnes and 12.7 million tonnes respectively, in 2023). More than 20 of the EAF steel facilities currently use coal to melt scrap metal. Steel is the country’s third largest export sector.

Turkey is one of the top five importers of Russian coal. Many countries, including the UK, EU member states and USA stopped buying Russian coal, as part of sanctions following the country’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

Vaibhav Raghunandan, from Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA) says, “Turkeyʼs increased reliance on Russian coal (and indeed other fossil fuels) is effectively tying it down to an increasingly volatile supplier who controls their market. The Russian coal sector is a huge source of revenue for the Kremlin and the Energy Ministry had set targets of attaining 25% of the global coal market by 2035. Taxes from coal constitute a significant part of the Federal Budget. Since the invasion, Turkey — A NATO country — has paid EUR 8.2 bn for Russian coal, which effectively finances Russiaʼs invasion of Ukraine.”

Since the invasion Turkey has increased its market share of Russian coal, Turkey’s imports constitute 13% of Russiaʼs total coal exports. In the first three quarters of 2024, Turkey has imported 15.7 million tonnes of Russian coal, making up 49% of Turkey’s total coal imports (valued at EUR 1.66 billion). This is an 82% increase when compared to the same period in the year prior to the invasion.

Additionally, the Russian coal mining industry causes cultural genocide, environmental destruction and air pollution issues, detailed in Coal Action Network and Fern’s report, Slow Death in Siberia.

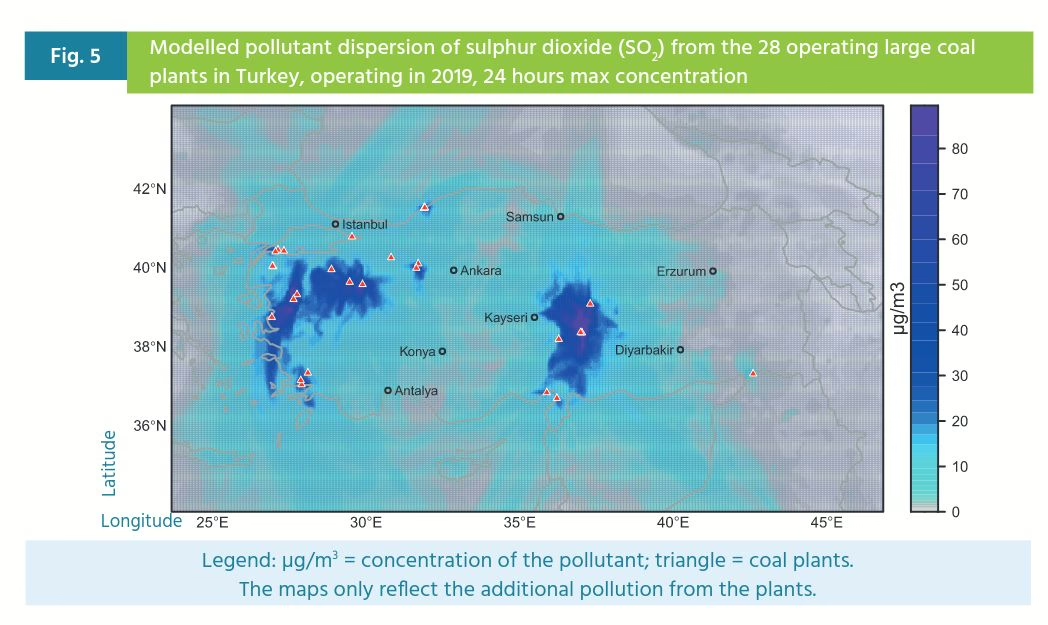

According to the World Health Organization, air pollution is the largest environmental threat to people’s health across the globe, including in Turkey. There are four main health harming pollutants released in coal consumption from steelworks and power stations: Sulphur dioxide (SO2); particulate matter – PM10 and the smaller PM2.5; nitrogen oxides (NOX) and mercury.

Breathing SO2, which is produced on combustion of high sulphur coal, increases the risk of health conditions – including stroke, heart disease, asthma, lung cancer and death. It is classified as very toxic when inhaled. Even a single exposure to a high concentration can cause a long-lasting condition like asthma. SO2 emissions rose by 14% in Turkey in 2019, one of the few countries in which emissions increased in that year. Coal-based energy production remains the major source of SO2 emissions in Turkey.

Local people in Ereğli, the city surrounding the Erdemir blast furnace steelworks, told Coal Action Network that university studies into their health are normally suppressed by government. However, in a study looking at the incidence of multiple sclerosis (MS) in populations in Ereğli compared to Devrek, which is a rural and clean city located 40 km away from Ereğli, “indicate a more than double MS prevalence rate in the area home to an iron and steel factory [Ereğli] when compared to the rural city [Devrek]. This supports the hypothesis that air pollution may be a possible etiological [Pertaining to, or inquiring into, causes] factor in MS.” Local people take no persuading that the air is contaminated by the steelworks and damaging their health.

Çetin Yılmaz, leader of Black Sea, Ereğli and Alaplı Environmental Volunteers, brought together 15 concerned citizens from Erdemir to talk with Coal Action Network about the impacts they face in the town surrounding the steelworks. They bemoan the scientific studies which show links between the steelworks and the diminishing health of the local population, but which are suppressed by the Government.

Çetin says, “The company [Eren Energy] has caused cancer in many people, it does not recognize the right of their employees to unionize in its facilities; it has fired workers who want to be unionized; it has made Çatalagzı into a breathless state; it has filled fish breeding grounds with ash; it burns 2 million tons of imported coal every year and caused the greatest damage to humans and nature in our region.”

A worker, who has worked at the Erdemir steelworks for 18 years, explained how he got throat cancer, which could be heard affecting his voice when we met him. Local people think 50% of the population’s health is affected by the steelworks. A teacher present recalled how in each of his classes around 10 children will have breathing issues, caused by the poor quality air.

The local political representative told Coal Action Network, “Most people here work in mines or in the steel plant, everyone knows that the air pollution causes cancer and breathing difficulties. The workers aren’t in a position to do anything about it as they have to earn money and would lose their employment, as well as their health.”

OYAK, the company which owns Erdemir and İsdemir blast furnaces, says it will use seven different methods to decarbonise. Its so called Net Zero Roadmap reads more like a list of potential options to reduce emissions and does nothing to resemble an actual plan.

Air pollution and health problems at İsdemir are likely to mimic those at Erdemir. Turkey’s CO2 intensity for the blast furnace steel production exceeds the comparable emissions for steel produced in Europe, the USA, and South Korea.

There have been persistent shortcomings in compliance with environmental, public, and occupational health regulations across the steel production value chain in Turkey.

Sitting at the eastern edge of Europe, Turkey is expected to surpass Germany as Europe's largest coal-fired electricity generator in 2024. Turkey is still opening new coal power stations, such as Hunutlu Thermal Power Plant opened in 2022. Turkey has 34 coal fired power stations, 10 use hard coal and the remainder use lignite, a less energy dense, poorer quality coal that is burnt close to its source. Two of the blast furnaces using coal also have coal power stations providing their electric.

Turkey’s electricity consumption has tripled in the last two decades, which has been underpinned by rapid growth in coal and gas generation.

As well as Ereğli, Coal Action Network visited three coal fired power stations near Muslu, called ZETES III and IV and Çatalağzı. All of the sites are within the district of Zonguldak.

Zonguldak was the only non-metropolitan district included in Turkey-wide weekend curfews for covid-19 reduction measures in 2020. This was due to pre-existing high rates of chronic respiratory diseases caused by poor air quality. According to local officials, it’s estimated that as much as 60% of the population displays some degree of respiratory symptoms, with mortality rates almost doubling between 2010 and 2020. The low air quality is caused by elevated levels of PM2.5 and SO2 pollutants from steelworks, coal mines and hard coal power plants.

The health costs from coal power generation in Turkey alone, are 26.07 - 53.60 billion Turkish Lire (2.86 - 5.88 billion €), which is equivalent to 13 - 27% of Turkey’s annual health expenditure.

Where Turkey significantly deviates from the rest of the EU in relation to steelworks and power stations is in the compliance and enforcement of air quality standards. As a report by Health and Environment Alliance (HEAL) shows, “While EU member states are legally required to report emissions at plant level to a publicly accessible database [...] Turkey does not share power plant or sectoral emission data. Instead, it reports merged data for electricity generation and the heating sector” This obscures the data. Furthermore, Turkey has not signed other important technical agreements to limit, and cooperate on, other pollutants. This includes three protocols on sulphur emissions (The 1985 Helsinki Protocol on the Reduction of Sulphur Emissions, the 1994 Oslo Protocol on Further Reduction of Sulphur Emissions, and the 1999 Gothenburg Protocol to Abate Acidification, Eutrophication and Ground-level ozone.). As HEAL states, “The lack of transparency prevents a rational and informed debate about improving air quality and health in the country.” Local people and ecosystems are left to deal with the consequences.

In the last 20 years, Turkey’s power plants that have been privatised and many do not use filter technology for SOx. They are the major contributor to Turkey’s increasing SOx pollution.

Everyone who spoke to Coal Action Network is worried about the air quality impacts of Turkey’s coal consuming plants. A resident living near three coal power stations on the Black Sea, near Zonguldak, says, “people believe that in some periods the air pollution filters on the plants are not working properly. Habitually, we have 250 days in a year the pollution is higher than the government’s acceptable standards.”

The consistent narrative from the residents overlooking either the steelworks or the coal power stations was one of poor air quality, resulting in higher rates of respiratory illness, cancers of various sorts, and death of plants and vegetation leading to an inability of local people to grow food.

In 2021, Turkey imported 36 million tonnes of coal for its power stations and steelworks, as well as using its domestically mined coal, which is mainly lignite, not used in steel-making. Turkish Coal Enterprises emphasises that the most significant increase in coal imports will come from the demand for electricity generation, and estimates that this trend will continue. Although President Erdoğan says the country will decarbonise by 2053 there is no meaningful road map to bring the blast furnaces into relevant carbon reduction strategies.

Barış Eceçelik from Ekosfer states, “Turkey is one of the few countries in Europe that has not set a date for the phase-out of coal. Last year, for the first time in the history of Turkey, imported coal became the leading energy source in electricity generation. Turkey has significant potential for renewable energy sources, including wind, solar, and biomass. However, the lack of a serious climate target and measures against coal usage has led to air pollution and a high level of energy dependence. It must be acknowledged that imported coal is not a solution to the issues of climate change nor air pollution.”

The pollution issues around the coal power stations do not just affect air quality. They also have a large impact on the Black Sea. The water around the power station is reported to be 4o warmer than elsewhere, as it is used in the power stations cooling processes and then returned warmed to the sea. Local people report seeing a sheen on the water from the heavy metals and other toxins which are released from the power stations. Burning coal high in sulphur increases sulphur dioxide which produces acid rain, and acidifies lakes and streams. Black Sea fishermen say that the power stations are damaging fish spawning grounds and reducing their catch. Food which is sold to Istanbul and Ankara.

Coal is a contested subject in Turkey. While people living close to existing coal facilities want the secure jobs, there are protests against new power stations and a proposed lignite power station was cancelled in 2013, following protests. Mining accidents are fairly common, with 301 killed in just one accident in Soma in 2014.

In the high up mountain village of Kokurdan (official name: Körpeoğlu) a coal ash and waste dump billows clouds of dust onto the dense trees surrounding the settling pool. Ash from the ZETES power stations and the dirt from the air filters are settled in a vast open dump. Although Coal Action Network visited immediately after heavy rain had washed the dust off the vegetation, homes and roads, the waste from ZETES coal power stations normally accumulates in the lungs, homes and crops of these people.

Villagers approached Coal Action Network to ask why we would want to visit their area when the coal facilities cause such contamination. “I hate being from here because of the pollution. When the weather is dry the dust covers everything.” one woman told Coal Action Network, whilst passing on the street in Kokurdan. In this village they are not convinced the damage is worth it because of the jobs. Local people say nothing good about the coal power plants, they just talked about the damaging health effects, adding liver cancer and stomach cancer to the list of illnesses caused by the coal power stations.

The most basic air pollution controls are not being implemented – lorries carrying coal are not even covered to prevent dust spreading along its route, a measure that long ago became standard in the UK. Public roads also run underneath the conveyor belts of ZETES power stations.

Monitors for fine dust particles known as PM10 are apparently not operational around the steelworks. PM2.5, is finer particulate matter that can penetrate the lungs and even enter the bloodstream and cause chronic diseases such as asthma, heart attack and bronchitis. PM2.5 is not monitored at all around Ereğli.

Coal Action Network’s visit to four coal facilities on the Black Sea showed that the human and environmental costs of burning coal are high. The issues of health, local environment and climate change are not being sufficiently addressed, but there is demand for improvement within Turkish communities living close to coal facilities.

In Spring 2024, Coal Action Network investigators visited Turkey to see first-hand the impacts that imported coal was having on communities living near steelworks and power stations using coal.

At that time, planning permission was in place for West Cumbria Mining Ltd to extract 2.78 million tonnes of coal a year, until 2049, from a coal mine under the sea near Whitehaven, Cumbria, UK.

The majority of the coal from Whitehaven would have been for export. However, the coal from Whitehaven has a high sulphur content, meaning European Union countries can’t use this coal in their blast furnaces due to air pollution standards and the UK blast furnaces will be replaced by Electric Arc Furnaces, to recycle scrap steel instead.

Therefore, of the countries listed by West Cumbria Mining Ltd as potential markets, only Turkey would have been a viable option.

Although the coal was considered to be coking coal, its actual end use would have depended on who bought it. Coking coal is a higher quality product, normally too expensive for power stations to use, but with its high sulphur content reducing price, Cumbrian coal could have been bought by Turkish power stations.

Shortly after our visit to Turkey, a General Election was announced in the UK. The victory by the Labour party, pushed out the Conservative Government which had approved the new coal mine in Whitehaven in December 2022.

Less than a month after the new Labour Government was formed, a court case was heard that had been brought by South Lakes Action on Climate Change and Friends of the Earth against the previous Conservative Government’s approval of the coal mine. The new Labour Government decided not to defend the previous Government’s decision to approve the coal mine. The Judge removed the planning permission for the coal mine in September 2024.

This momentous decision was reinforced by the Coal Authority subsequently declining the license application for the coal mine. There remains a final decision from the Labour Government regarding the application, but it is considered very unlikely to win the required permissions now.

We’re publishing this article on Turkey’s coal use because of the generous help that we received from Turkish people during our investigation, although it is no longer part of an active UK campaign.

The scientific consensus is that we need to decarbonise heavy industry. Steelworks are amongst the worst carbon emitters. Both of the UK steelworks using coal have agreed to convert to electric arc furnaces, a process which sadly requires far fewer steelworkers. When Port Talbot stopped its coal consuming blast furnaces at the end of September there was a poor deal for the workers. British Steel and the government must do better for the workers at Scunthorpe’s steelworks, expected to turn off the blast furnaces by the end of the year.

Former steelworker, Pat Carr, spoke to Anne Harris from Coal Action Network about the financial support offered to workers when the Consett steelworks closed in 1980, and they discussed what can be done better, in workplaces like Scunthorpe steelworks.

Read the full article, in the Canary Magazine from this link

Pat Carr is a resident of Dipton, County Durham, he worked, alongside many members of his family at Consett Steelworks, before it was closed down. In 1980 the Nationalised British Steel Corporation sought to prioritise coastal steelworks that could more easily import iron ore and export finished products, which was the end of the inland steelworks.

Below is the transcription of an interview of Pat Carr, with his son Liam by Clara Paillard (Tipping Point) and Anne Harris (Coal Action Network).

Coal Action Network was interested to find out what was successful about the redundancy package for workers being let go as Consett steelworks closed and what lessons can be learnt for a truly Just Transition of current high carbon industries, such as Scunthorpe steelworks, making redundancies or closing due to the climate crisis. We are worried that the workers at Scunthorpe will suffer the same poor deal of workers at Port Talbot, as both blast furnace steelworks are converting to produce steel using electric arc furnaces rather than blast furnaces using coal.

(Transcription of the interview, edited lightly for clarity. To listen to the recording click here.)

Question: Can you give us an introduction?

“I worked in the steelworks for 11 years. In the steelworks, as a steelworks operative you start as a labourer and then you filled in for all the different jobs on a day by day basis, until you picked a line that you wanted to go into. So you could be on the furnaces or... or boiler cleaning, so there are lots of different lines of labouring type work. And I was on the furnace line… I was the senior labourer there. Therefore you got the first job choice for each day. The system was that you had a lieu day, each worker was on a 40 hour week, therefore it was a constant shift system... Each job had to be filled on that rota. Each day you checked who was in and who was on sick, checked all the cards, saw where the vacancies were, the different roles in the steelworks and then you filled them in down the line, so each of the labourers did that. So, that’s what I did for 11 years, but mostly on the furnaces, the O2 furnaces.”

“... Yeah, you change shifts every two days. So you might be on night shift Monday, Tuesday, and then you might go back to 2pm -10pm Wednesday, Thursday, then you’d be 6 o’clock in the morning until 2 in the afternoon Friday, Saturday, Sunday, Then you get your two days off. So you change shifts constantly."

Question: You must have been a young man when you started, how old were you?

"20 years old."

Question: Am I right to say that at the time it was still the British Steel Corporation? It was still a nationalised company?

"Yeah, the British Steel Corporation, yeah. That was the organisation yes."

Question: When you started at 20 did you think that was going to be a job you’d be in for a long time? Or was 11 years quite good innings?

“I just needed a job, so I just took it at that age. I’d previously been a student and it hadn’t worked out. Thought I might want to go into teaching but I decided I didn’t want to, so that didn’t work out. So, I ended up in the steel works at that age… I was made was made redundant once during that time, the steelworks has always been a strange industry of peaks and troughs. Lots of people who were started there were taken back on and so was I... There was one time, after a couple years where I was made redundant, but it was only for a 6 week period, then trade picked up again and you’re taken back on and end up in the same place.”

“In our street there was me and my brother. And my father had been a miner but then he ended up in the steelworks as the mines were closing down, but he started after me. My brother he worked elsewhere and then he ended up there, laying train tracks in the steelworks. My cousins down the street, they lived a few doors away from us. and their father worked in the steel works, their mother worked in the steel works. My closest cousin, who was about the same age as me, he started at the same time as me and we went through all the steelworks together for 11 years together. His brothers worked in the steelworks and his sister worked in the steelworks cos she was a nurse and she worked in the medical centre in the steelworks. So that was a whole family virtually, two adults and six siblings. Lots of families. Women worked all over the steelworks.”

Question: Were workers members of a trade union, and if so, which one?

"It was called BISAKTA when it started, British Iron, Steel and Kindred Trades Association. Then it became ISTC. [Iron steel trades confederation.] They just changed the name slightly. Iron Steel Trades Confederation.”

Liam “Did it turn to GMB in the end?”

“No, I’ve no idea what it is now. I don’t know how many steelworkers there are left, probably very few.”

Question: there are still some, a big union representing steelworkers is called Community it is probably one of the decedents of the unions you mentioned.

“It was the ISTC in 1980.”

Questioner: When steelworks were up for complete closure what happened? What was the year that it happened, why did it happen? How did people in the community or workers respond to that decision?

“There had been a miners strike the year before, we were then on strike earlier that year for the early part of that year. We were on strike for 10 weeks or something like that. In the winter of that year and there had been talk of closures all over the place and we were still trying to campaign to keep the Consett steelworks open. But I think it is a wearing down process… our family were all still resolute that they should be kept open. But there were others that were starting to waive and then they started to offer all kinds of incentives to take redundancy payments, enhanced payments, training schemes and all kinds of things, which may have swayed some of them. As far as I recall that took maybe eight months of negotiation, including marches in London and marches in the locale. Eventually the closure was complete in about September that year.”

Question: during that time when they were trying to close the steelworks, were people arguing that there should be a Just Transition and training, or were people just saying that it shouldn’t close at all?

“There were a lot of people campaigning that it shouldn’t close at all, that it was so crucial to the local economy. Although, there was maybe 3,500 people working in the steelworks itself there was probably another 3,500 people that were dependent on that with all the transport links and ancillary works that went on and all the contractors that were brought in to do other tasks. So there was probably almost twice as many were involved but didn’t have a say, because they weren’t directly involved in the steelworks.”

“Just prior to that, the year before they did close Hownsgill steel, they had a big plate mill. It’s a massive complex a steelworks, so you have the iron making and then that moves onto the steelmaking, and that rolls into ingots that can be made into other things. And then some of the steel was sent up to Hownsgill that was just another part of the steelworks, where it was rolled into plate...maybe 40 foot long plates, maybe an inch thick and 6 feet wide, or something like that. So all these plates were rolled there, and the year before there was an argument put that if Hownsgill wasn’t part of the same scheme, if they closed Hownsgill, then the rest of the steelworks could be viable… It was supposed to make us more viable, but as it proved it didn’t matter that much. All that meant was that all those people at Hownsgill didn’t get the same terms and conditions that we came out with, because we had a national negotiation closing the whole steelworks and they never got that. So they went on much inferior terms to the rest of the site than the rest of the steelworks got for want of a year’s grace.”

“The redundancy payments if I can recall were quite generous. Virtually everyone in the steelworks, even if you’d been there a year or two you got 6 months pay and I’m not sure you didn’t get another six months pay a year later. So I think that was part of it. It was quite good for that time and absolutely incredible for this time to get a year’s money. So that was a bit of a sweetener. So that was redundancy payments, or severance pay I think it was called at the time. Cos redundancy payment was a nation scheme and the severance pay was enacted through the union and the steel corporation… then you got your ordinary redundancy was calculated on top of that, you got maybe a week and a half for every year that you worked in the steelworks. So that was an extra payment on top, and if you had another job to go to that sounds OK, it was a pretty good sweetener. An extra year’s money, plus another job on a similar basis, but unfortunately, the vast majority of people didn’t have that other job to go to.”

“For the year afterwards it was a bit of a boom town because of course all this money was swilling around, everybody had more money that they’d ever had, in cold hard cash, but without the prospect of it going on. It meant people were getting new cars, I think a lot of the local garages did very well out of it for instance for a couple years. You could put a deposit down on your house, or start buying your council house that kinda thing. It was a bit of sweetener for some. But that’s fine if you’re 60, you’re old, and you get that, and your pension isn’t too far away. Then it seems to work OK, but if you’re 20, 25 or 30, then you’ve got the whole of your working life ahead of you... If you wanted that role to be out in the steelworks, then that was never going to be the option again.”

“We got severance money, we got our redundancy money and, if you went on a training scheme, any recognised training scheme, you got your normal wages that you got in the steelworks for the time you were in the training scheme, for up to one year. That was another year’s bonus where you could go into virtually any eduction scheme. So that was another boom area… they were putting courses on for everybody to do anything. No matter if you had any prospects in it or you were even interested in it, you were a fool not to go onto it cos it meant that you could get a year’s money which you weren’t having to sign on the dole.”

“The local further education was at Consett Technical College, they started running courses all over the place so that they used Working Men’s social clubs, in any old schools, any old buildings that they could put 10-15 steelworks and the tutor they got the money for that. And the steelworkers got the money for it as well, so they were paid their normal wage, so everybody was into education for one year.”

“I’m guessing the money came through the British Steel Corporation because I haven’t heard of it being done anywhere else, so I’m guessing it came through British Steel Corporation and through the government as well. I think there must have been a government incentive to try as at the time they were trying to shut down all sorts of things. It was the time when Thatcher was just about getting into her stride… It was the same feller who went on to the mining [Liam interrupts with “MacGregor”] MacGregor yeah, I think he was working on closing the steelworks at the same time as he was being groomed to sort out the national coal board at the same time.”

“I went down to, it is Sunderland University now. I was doing data processing, it’s an IT course, computer science, it was a degree course… But my father went, he wasn’t very, he wasn’t a great scholar in his youth and he was barely literate, but he went on a course because it was a free year."

"So you go on a reading and writing course, any course, but I actually did a degree in data processing and ended up in computers, computing...and that’s what I worked in most of the time since then, either computer programming or systems analysis, that kind of work.”

“My brother did much the same, but he went straight into, I’m not sure he did the training but he got a job at the national [….] but on the computer side. My cousin who lived down the street, he came with me on the same course, so we ended up doing the same course. We didn’t do the first year, but we ended up on the same course again… There was some who saw a career opportunity and others who wanted the money regardless. If you were 55, which I think that me father would have been by then probably, he needed the year’s money so he went straight into that, and he did a course just because cos it was a simple way to keep the wolf from the door.”

“There might have been a cut off time of a year” [working at the steelworks to get the money to retrain]

“Literacy courses were just as vital as any higher level courses, they were just as vital to those people… It was an absolute boom time. My father did his course in the working Men’s Club, there wasn’t enough facilities to cater for everyone who wanted to do the courses.”

Question - what was the role of the unions?

“I’m not certain who was doing that negotiation, but I think that that was the sweetener because I’m not sure there was a massive vote and they voted to close that plant in the end. Because it must have been close to it, a 50 : 50 split as to close the place or keep fighting on and possibly loose all of those enhanced conditions. Or whether just to hold up and take the enhanced conditions. I was never quite sure if there was a vote on that and that’s the way it went eventually. There wasn’t a prescribed vote on that. There was never a sheet of paper, I think there would just be a show of hands in a mass meeting.”

“It’s the best one I have heard of, I’m not sure what the pit closures got. It must have been around the same time as pit closures, or in the next four years, but I don’t think they got that same enhancement.”

Question: What could be learnt for current transitions?

“Certainly the education and training certainly helped me massively. I would never have thought of going into it, I always had at the back of my mind that I could have been doing something other than working at the steelworks, but I wouldn’t have jumped ship because the jobs was so good and the money was so good in the steelworks, so you would never leave it on that basis. Having been pushed into it, it wasn’t the most dreadful thing that happened to me. It worked out not too bad."

"There were hickups, it wasn’t all plain sailing so the first job didn’t work out that I got after qualifying... The eduction did work out for me long term, that’s what I needed at that time. We’d just had our 4th child so I needed a job at the end of the education... it had to have a concrete task at the end of it. And actually it… was quite good because the course that I went on, as well doing your 3 years, it was a sandwich course. So I also had one year out in industry, which meant I earned the money for that year. And therefore I got an extra year earning at the same time as the education was going on. So that worked out quite well as well.”

“I did a three year course with a year in industry where you were out and working for the year, so you got the wages as well so you weren’t reliant on… at the time I think I could claim unemployment whilst at college cos the hours were, the attendance hours weren’t massive. So you could still register as unemployed, I’m not sure it was legal or not, but it was the route I took. So I could claim unemployment benefit whilst still attending college.”

What was the situation 5 years on?

“It was definitely boom and bust, after that one of the local politicians said it used to be a BSc town, but now it’s a MSC town, meaning Manpowered Services commission, cos there was a time when if you registered unemployed they sent you on all kinds of retraining courses, which were unusually insignificant but I think that after that first 4- 5 years it definitely took a slump, the local economy. It’s virtually a dormitory town now, everyone travels to work.”

“There are industrial estates.. there were things brought in, probably on grants. Electrac which was supposedly a new form of electricity supply to your home where you could plug in anywhere in any room which sounds quite attractive now...There were some bits and pieces that came in, a little portion of the aerospace industry that came into an industrial estate in Consett, but never with the scale of the steelworks. Maybe a hundred workers would maybe be the size. Some food industries came.”

“They were probably dragged in with government incentives as it was now in a dire state economically and so there were extra incentives to bring those works into the area.”

Question - Was there new industry created locally?

“One or two of my friends went down to Teeside cos there was still a steelworks in Teeside. And they worked down there on the new steelworks down there. But not a lot, I’d guess way less than 1% actually went to Teeside.”

“There was nowhere, if the steel industry is suffering in one area it’s not going to be suffering everywhere. If it’s not going well in Consett it won’t be going well in Teeside either. All they were doing was filling in jobs, vacancies where if they knew that role they could move into that.”

“Actually I did know one lad who went to Mexico to build steelworks. I think British Steel Corporation were being employed to build new steelworks in different areas of the world in the far east and Mexico and they were building that while undercutting themselves. So there were some people who did that, went away. Then there were some people who were working on pulling the steelworks down cos that was a massive project, it was an absolutely gigantic project Project Genesis it’s still going on now, I’m not sure it’s ever going to finish. But the actual pulling down that took at least 5 years and then pulling up all the rail lines and that kind of things, you loose your railways as well. Because that was just there to serve steelworks… it was only goods at that time. The last passenger was prince Charles just after the closure. And they ran a passenger train. King Charles as he is now, I think it was the only passenger train that ran for several years…”

Anne says it makes it hard to go to work if you lose the rail station.

“Luckily, my cousin went the same place and I knew people around the area who were all going down to Sunderland so we used to share journeys down there.”

“It’s hard to extrapolate now as you’ve seen virtually every centre in Great Britain fall prey to all kinds of things… it probably had a boost for about 2 years and then it slowly drifted down and became less and less viable to shop in Consett and the centre its self. And at the same time there was lots of out of centre shopping being brought in... The middle of Consett isn’t too badly served with large shops, you’re still within walking distance of the centre of Consett to a lot of the super markets so but the main streets, the main streets everywhere are struggling. I think the pub trade took a hit, it took a massive boost and then of course, it took a massive hit after 4 or 5 years so instead of being 20 pubs in Consett there is probably 10 now.”

Question - Would you have stayed in the industry if you could?

“Absolutely not.. I enjoyed the work and I enjoyed working at the steelworks and I enjoyed working on the furnaces. There was always a slight niggle at the back of your head that you should be doing something else, but it was good work and good money, so I would never have moved. The first job I got after that I was having a cuppa and the boss came in and said “this is different from what you used to do”. It was my first job in Tyne and Wear and I said, “yeah it is different” and he said “this is far better isn’t it I bet you’re glad you’re doing this”, and I said, “actually I wish I was night shift going to the steelworks,” and that was about four years after I’d finished.”

Question - What messages do you have for current workers in high emissions industries?

“I would hope the allied industries would pick up on that, so you’d hope that the green side of that same industry would pick up some of the slack and maybe that’s where the retraining should be focussed and move onto that side rather than persevere with the one we’ve got.”

Clara says report published by climate orgs working with oil workers and 80% of oil and gas workers would be open to retraining. Anticipating collapse.

“Although there must have been pre-planning that we weren’t involved with, you never saw that… It was as good a deal as I’ve seen anywhere the scheme that we got. I don’t think it is has bettered since and I doubt it has been approached since.”

Clara says we will bring this back the message of what you benefited from at the time to those working on Just Transition in oil and gas industries.

Anne - we're working against 2 coal mines and for decarbonisation of the two major steelworks using coal. The company and the government aren't really giving the workers any kind of transition period. They are sort of blaming activists for steeling jobs, when the coal mine was supposed to close [Ffos-y-fran].

“It was always a bit of an incentive,... when Joanne was on planning at the Council and they were looking for opencast permissions and they used to send workers from Banks to the house and they to say, “what we could do is have more workers here and 10 workers or something.” and I used to think, “yeah, you can have 10 workers, but bleeding heck, it was an absolute drop in the ocean compared with what had been in pit”... It was just a sock for those workers and I think they were being used by the management onto decision makers and local authorities. It was hard to put an argument against them because they had such a vested interest in it. They saw it as you taking their job away. They were different times.”

===Ends===

Port Talbot Steelworks in South Wales is the largest producer of virgin steel in the UK. Along with British Steel steelworks in Scunthorpe, Port Talbot steelworks is expected to shut down its blast furnaces in 2024 and build a 3 million tonne (MT) electric arc furnace (EAF) to recycle scrap steel. This is a measure to reduce the steelworks CO2 footprint by cutting out coal used in traditional blast furnaces in virgin steelmaking.

In ‘A workers’ plan for Port Talbot’, the UNITE workers’ union points out “The government's current proposal is to give a handout to Tata [Port Talbot Steelworks], without asking for any conditions to protect jobs.” On 15th September 2023, this handout was confirmed at £500 million with expected job losses up to 3,000. The deal was reached without meaningful union or worker involvement, despite those workers facing the biggest upheaval at the steelworks.

We share the Unite union’s conviction that the low-carbon transition at Port Talbot Steelworks can, and must, be a just transition. In its workers’ plan, Unite point out that only 60% of UK steel demand is met by domestic production, and that the UK imports 10 out of 17 main steel products. By 2035 demand for green steel could rise as high as 19.4MT, according to Unite. In 2022, the UK produced 6MT of steel. These figures underpin Unite’s case for expanding EAFs at Port Talbot to 6MT-9MT, beyond the current conversion plans of a 3MT EAF.

Unite’s proposed expansion—together with scrap steel processing jobs to improve scrap input quality—would retain, or increase, jobs at the site of Port Talbot steelworks. Unite states that diverting the amount of scrap the UK exports each year would provide sufficient quantities of scrap steel to expand the EAF capacity for Britain’s green steel sector.

Beyond EAFs, Unite is pushing the UK Government to invest in, and develop, emerging technologies like Hydrogen Direct Reduced Iron (HDRI) to produce virgin steel. The large amounts of electricity needed to support that could, according to Unite, be produced sustainably by constructing a floating windfarm just off the coast of Port Talbot, which it claims has suitable topography. This could safeguard more jobs and contribute to reducing the carbon footprint of other carbon intensive industries, such as cement and ammonia production.

Unite estimates that HDRI roll-out would require a public investment of around £1 billion per year over the next 12 years. That may sound like a lot but, in total, that amounts to a billion less than the widely derided Test and Trace app cost in its first year alone.

CAN advocates for a variety of strategies to meet UK steel demand into the future, including efficiency, recycling, technology, and more selective production. But where there remains a demand gap, production should be coal-free and utilise a circular economy based on safer, desirable, and dignified jobs within the UK. We also believe it’s vital that the impacts of steel production are not just considered at the point where iron or scrap arrives at steelworks.

Upstream extractive industries and scrap steel sorting and processing underpin, and are impacted by, changes at steelworks. The environmental and economic consequences for these upstream sectors means mine workers and community members living on the frontlines of iron and coal extraction, and the consequences of climate change, also need to be part of the conversation, as stakeholders, for a truly just transition.

CAN agrees with the Unite union on the following demands:

Published: 18. 12. 2023

People hailing from Cumbria to London, and everywhere in between, descended on the Mines and Money Conference in London across two days (28th-29th Nov 2023). We demanded that investors stop pouring cash into the mining sector, and instead invest in our collective future. Together with Fossil Free London and other groups, we greeted investors with flyers highlighting risks to investments in mining that mining companies want to hide—such as successful grassroots resistance to mining projects around the world.

We also heard on the grapevine that EMR Capital PTY, the ultimate owner of the proposed West Cumbria coal mine (WCM), was attending in the desperate hope of raising the £230 million still needed to start the WCM. So local campaigners from Cumbria came all the way to London to deliver a message to potential investors in WCM—steer clear! To further ruin EMR Capital PTY’s plans, they also handed investors a risk assessment, provided by BankTrack, outlining risks specific to the proposed WCM proposal. Two other coal mining companies were present at the conference too.

There’s many alternatives we must take instead of clawing the ground up to reach the minerals beneath, and that is where investment is needed. For example, we need:

This would truly be ‘resourcing tomorrow’—the strapline for this year’s Money & Mining conference. Instead, the conference encourages investment in the rush for remaining minerals, fuelling human rights abuses, land grabs, destruction of local eco-systems, and climate change.

We call out the host of this disastrous conference, the Business Design Centre, which boasts its ethical ‘B-Corp’ status. You might want to raise your concerns with the certifying body about giving these hosts any kind of ethical certification (certification@bcorporation.uk), pointing out that at least three fossil fuel companies advertising coal mines and oil production were touting for investment at the conference (BHP, ADX Energy, and Teck).