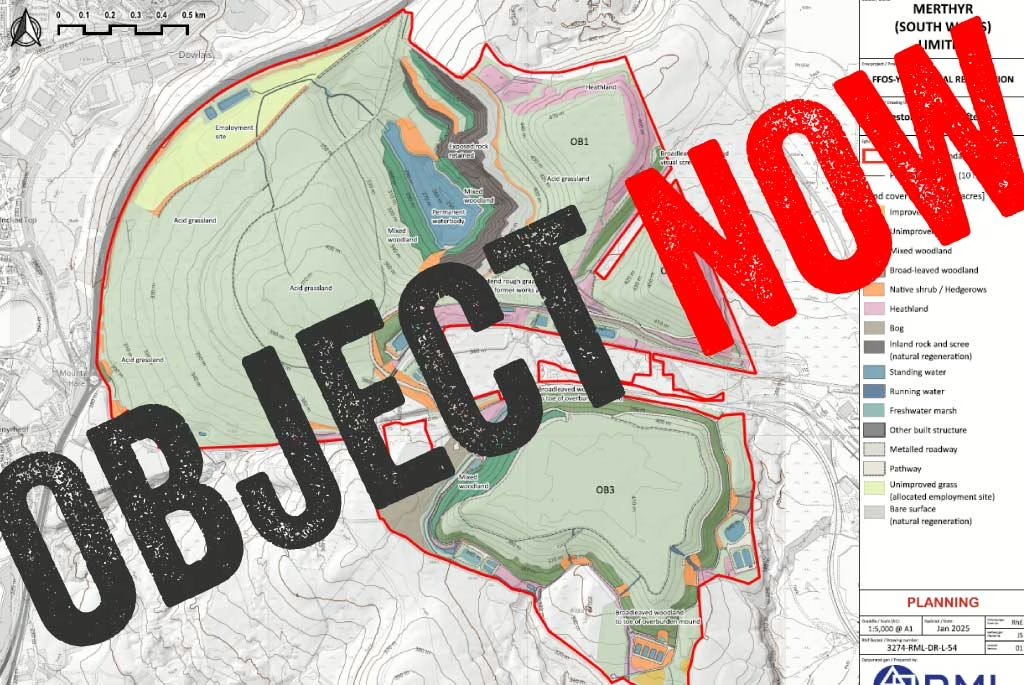

IN THE MATTER OF FFOS-Y-FRAN COAL MINE

AND IN THE MATTER OF THE TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING ACT 1990

OPINION

For correct paragraph numbering, please refer to the PDF.

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY

We are asked by Coal Action Network for our opinion on the ongoing situation at Ffos-y-Fran coal mine, Merthyr Tydfil (‘the Site’). In particular, we are asked for our opinion on the past and future exercise of statutory enforcement powers by Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council (‘the Council’) and the Welsh Ministers.

- In summary, the site has been used as a coal mine since 2005. On 6 September 2022, planning permission for the extraction of coal from the Site expired. Merthyr (South Wales) Limited (‘MSWL’) did not, however, bring its coaling operations to an end and continued to extract coal from the Site in breach of planning control. No enforcement action was taken by the Council or the Welsh Ministers in relation to this breach for eight-and-a-half months. An enforcement notice (‘the EN’) was finally served on 24 May 2023 with compliance required by 22 July 2023. No stop notice has been served. If MSWL appeals against the EN, the EN will not take effect until the determination of that appeal which, on current timescales, may take around 12 months. Consequently, in the absence of a stop notice, the Council and the Welsh Ministers may have enabled MSWL to extract coal, without permission but without consequence, for more than 18 months.

- Coal Authority data shows that MSWL extracted 168,862 tonnes of coal, without permission, in the six-month period from 1 October 2022 – 31 March 2023. If extraction continues at the same rate, MSWL may extract around half a million tonnes of coal in the 18 months from 6 September 2022 until the EN might take effect. The total emissions attributable to 18-months of unlawful coaling at this single mine are in the region of 2 million tonnes CO2eq, the equivalent of the annual emissions of 155,000 people in Wales.[1]

- The extraction of the coal and the associated emissions are the result of a mining company choosing to act unilaterally and unlawfully. The activity has not been approved by any democratically elected bodies or persons.[2] It is not subject to any mitigations imposed by planning condition or obligation. It is wholly unauthorised and unconstrained. But on the approach adopted to date by the Council and the Welsh Ministers there will be no consequence for that unauthorised and unconstrained activity and no deterrent effect to dissuade future operators from acting in the same way.

- Planning Policy Wales and the Welsh Ministers’ Coal Policy Statement acknowledge a climate emergency and impose a strong presumption against permission for coal extraction. The Council has determined that the ongoing activity at the Site is not acceptable in planning terms. But the Council and the Welsh Ministers have failed to take action to bring the unauthorised activity to an end urgently and decisively. Instead, they have treated a breach of planning control related to the extraction of coal in the same way they would treat a breach of planning control related to the erection of an unauthorised building. These are, however, fundamentally different things. The planning harm caused by an unauthorised building can be remedied by the building’s ultimate removal. In contrast the planning harm caused by the unauthorised extraction of coal cannot: the coal cannot be put back in the ground; the carbon emissions from burning the coal cannot be removed from the atmosphere.

- In the circumstances, it is arguable that the Council’s and Welsh Ministers’ eight-and-a-half month delay in taking enforcement action was unlawful. Further, it is strongly arguable that it would be unlawful for the Council and/or Welsh Ministers to fail to serve a stop notice by 27 June 2023, the date on which the EN is due to take effect.

- Irrespective of the lawfulness of the Council’s and Welsh Minister’s past and future exercise of their enforcement functions, it is clear to us that their failure to take urgent and decisive enforcement action against the breach of planning control in this case constitutes maladministration and sets a terrible precedent. It sends a message to all mine operators in Wales that there is no need to bring operations to an end when planning permission expires because the planning system can be ‘gamed’ to enable continued operations for an extended period beyond that date with no consequence.

THE FACTS

- MSWL extracts coal from the Site for use in industrial and non-industrial uses.

- Planning permission for the extraction of coal on the Site was first granted on 11 April 2005 by way of appeal decision APP 152-07-014. That permission was varied pursuant to a further appeal decision dated 6 May 2011 (“the Planning Permission”). Conditions 3 and 4 of the Planning Permission required extraction from the Site to cease no later than 6 September 2022 and site restoration to be completed by 6 December 2024.

- On 1 September 2022, five days short of the date by which all extraction was to cease, MSWL sought permission under section 73 of the Town and Country Planning Act to extend the date by which extraction from the Site must cease to 6 June 2023 and the date by which site restoration must be completed to 6 September 2025 (“the Planning Application”).[3]

- The Planning Application was accompanied by an addendum to the environmental statement prepared in 2005 (‘the ES Addendum’), but not by a full environmental statement. The 2005 environmental statement did not address the climate change impacts of the development and nor did the ES Addendum: there is no assessment of the likely greenhouse gas emissions attributable to the proposed extension of the life of the development.

- Extraction of coal from the Site continued beyond 6 September 2022 in breach of planning control. As early as 12 September 2022, the Council began to receive reports of continued coaling on the Site in breach of planning control. On 27 September 2022, local residents were supplied with a statement from the Council via their Assembly Member stating:

“If coal mining operations continue on site, this would result in a breach of the planning conditions and may be subject to enforcement action. At this stage because a planning application has been submitted, which seeks to amend to the current permission and enable operations to continue on site, it would not normally be expedient to take enforcement action until that application has been determined…”

- The Council’s position, therefore, was that it would consider the expediency of enforcement action only after considering the acceptability, in planning terms, of the proposed development.

- On 18 October 2022, the Welsh Ministers issued a holding direction under Article 18(1) of the Town and Country Planning (Development Management Procedure) (Wales) Order 2012. The effect of the direction was to restrict the ability of the Council to grant planning permission until the Welsh Ministers had considered whether to exercise their call-in powers to determine the Planning Application themselves.

- On 21 December 2022, the Council issued a screening opinion (‘the First Screening Opinion’). On the basis that the proposal was to extend for nine months development that had previously been assessed as acceptable (subject to mitigation), it concluded that the proposed extension was not EIA development. It said:

In conclusion, the Authority is of the opinion that the proposed development, either alone or in combination, is unlikely to have a significant adverse effect on the environment. The extension of 9 months to complete the development previously approved will extend the impacts of the development. However, these impacts have previously been assessed as being at an acceptable level subject to mitigation and limitations provided by planning conditions. There is no proposed change to the method of working and therefore no environmental impacts are envisaged over and above those experienced as part of the 2005 planning permission. As such, the likely effect of the development is unlikely to be significant enough to warrant an EIA.

The First Screening Opinion did not address the climate change impacts of, or greenhouse gas emissions attributable to, the proposed extended life of the development.

- On 12 January 2023, Coal Action Network wrote to the Council to seek confirmation of whether active coal mining had continued at the Site beyond 6 September 2022. On 20 January 2023, David Cross, Principal Planning Officer at the Council, replied, confirming that the Council understood – apparently on the basis of information provided by MSWL – that coal mining had ceased on the Site, pending the outcome of the Planning Application. That understanding was wrong. Active mining had taken place regularly since 6 September 2022. The Coal Authority’s production data demonstrates that MSWL extracted 102,505 tonnes of coal from the Site between 1 October and 31 December 2022, without planning permission.

- On 30 January 2023, Coal Action Network drew the Council’s attention to the Coal Authority evidence. On 2 February 2023, David Cross replied to say that he would review the information provided and would consider whether to escalate the matter with the Council’s enforcement team.

- On 3 March 2023, Richard Buxton solicitors (“RBS”) wrote to the Town Planning Division of the Council on behalf of Coal Action Network to request urgent enforcement action in relation to the ongoing breach of planning control. The letter set out why planning policy demanded enforcement action in this case and why any delay would render enforcement action nugatory. Noting that the Planning Application sought an extension of coaling to 6 June 2023, and noting that MSWL has already, by default, enjoyed six of those nine months of coaling, it said: “the development will soon effectively have been carried out without permission and the harm identified in Welsh Policy irrevocably caused, regardless of the decision that may eventually be made on the extension application.”

- The letter was copied to Welsh Ministers and noted that if the Council delayed in taking, or declined to take, enforcement action, Welsh Ministers would be asked to exercise their own enforcement powers.

- On 9 March 2023, solicitor to the Council, Geraint Morgan, replied to RBS, informing them that “the Council does not consider it would be a productive use of its officers’ time to provide a detailed response at present to the matters raised in the [RBS] letter.” It continued to note that the Council’s planning committee would consider the section 73 application on 26 April 2023 and “any issues pertinent to enforcement will be taken in light of the decision that is made by committee”.

- On 13 March 2023, RBS wrote to the Welsh Ministers drawing their attention to the ongoing breach of planning control, copying the correspondence between RBS and the Council and seeking the exercise of enforcement powers by Welsh Ministers. No response was received to that letter.

- On 31 March 2023, David Cross wrote to Coal Action Network confirming the following: “Whilst we were under the impression that the majority of the works being undertaken on site sought to address the slippages, and in part, works associated with the restoration of the site, it now appears that coal extraction has also continued alongside these activities.”

- Indeed, the Coal Authority’s production data shows that, in addition to the 102,505 tonnes of coal extracted from the Site between 1 October and 31 December 2022, MSWL had extracted a further 66,357 tonnes of coal, without permission, between 1 January and 31 March 2023. Notwithstanding this, Mr Cross confirmed the position as set out in the Council’s 9 March letter to RBS, namely that “any issues pertinent to enforcement” would only be considered after 26 April 2023, once the Council had resolved whether it would grant the Planning Application.

- On 3 April 2023, RBS wrote a pre-action letter to the Council and the Welsh Ministers alleging that the Council had acted unlawfully by: i) failing to consider enforcement action as a prior and separate question to whether to grant planning permission; and/or ii) failing to take enforcement action against the ongoing breach of planning control. The letter also alleged that the Welsh Ministers had acted unlawfully by failing to take any steps in relation to the ongoing breach of planning control.

- On 11 April 2023 and 22 April 2023 respectively the Council and the Welsh Ministers provided responses to RBS’s pre-action letter and denied they had acted unlawfully. The Welsh Ministers maintained it was reasonable to wait for the Council to take a decision on the Planning Application before consideration of enforcement and asserted that the scheme of the legislation “makes it clear that the local planning authority is the principal decision maker in relation to [enforcement] functions”.

- On 11 April 2023, the Council gave notification that MSWL had varied the Planning Application and now sought permission for an extension of coaling to 31 March 2024. No update to the ES Addendum was provided, notwithstanding the additional nine months of coaling proposed. On 18 April 2023, the Council issued a further screening opinion (‘the Second Screening Opinion’) concluding that the further proposed extension was not EIA development because:

“The extension of extraction operations until 31 March 2024 and a delay in the completion of final restoration until 30 June 2026 in order to complete the development previously approved will extend the impacts of the development. However, these impacts have previously been assessed as being at an acceptable level subject to mitigation and limitations provided by planning conditions. There is no proposed change to the method of working and therefore no environmental impacts are envisaged over and above those experienced as part of the 2005 planning permission. As such, the likely effect of the development is unlikely to be significant enough to warrant an EIA.”

The Second Screening Opinion did not address the climate change impacts of the proposed extended life of the development.

- On 17 April 2023, the Council’s Planning Officer, Judith Jones, prepared a report for the Planning Committee, recommending the Committee refuse permission for the Planning Application, as varied. On 25 April 2023, the Planning Committee unanimously voted to refuse permission for the Planning Application, as varied. The reasons for refusal were set out in a decision notice dated 27 April 2023, which stated:

- “The proposed development fails to clearly demonstrate that the extraction of coal is required to support industrial non-energy generating uses; that extraction is required in the context of decarbonisation and climate change emission reduction; to ensure the safe winding-down of mining operations or site remediation; or that the extraction contributes to Welsh prosperity and a globally responsible Wales. The proposed development therefore, fails to meet the test of 'wholly exceptional circumstances,' contrary to Planning Policy Wales 11, the Coal Policy Statement and Policy EcW11 of the Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council Replacement Local Development Plan 2016-2031.

- The proposed development fails to provide an adequate contribution towards the restoration, aftercare and after-use of the site, to the detriment of the surrounding environment, contrary to the requirements of Policies EnW5 and EcW11 of the Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council Replacement Local Development Plan 2016-2031. Therefore, no local or community benefits would be provided that clearly outweigh the disbenefits of the lasting environmental harm of the development.”

- On 27 April 2023, RBS wrote to the Council and Welsh Ministers seeking urgent enforcement action, involving the service of a temporary stop notice to ensure the unconsented activity was brought to an end immediately, followed by the service of an enforcement notice as soon as the expediency of such a course was determined.

- On 28 April 2023, the Welsh Ministers indicated that it was for the Council to decide whether to take enforcement action and only once it had taken a decision would the Welsh Ministers consider enforcement action.

- On 2 May 2023, the Council replied indicating that it had commenced an enforcement investigation and would not comment further until the conclusion of that investigation. There is no evidence that the Council had taken any significant steps to investigate enforcement prior to the refusal of planning permission.

- In May 2023, the Coal Authority inspected the Site and found the operator working coal, without planning permission and beyond the agreed licence boundary.

- On 24 May 2023, the Council served the EN requiring MSWL and any other person with an interest in the Site to cease the extraction of coal from the Site and cease carrying out development at the Site other than wholly in accordance with the approved restoration and management strategy. The EN, as drafted, takes effect on 27 June 2023 with compliance required within a further 28 days. That means that it will be a criminal offence to continue coaling beyond 25 July, unless an appeal is made against the EN.

- We have been provided with drone footage which appears to show the continuation of active coaling on the site as late as 15 June 2023. [4] Despite requests to do so the Council has failed to serve a stop notice requiring the cessation of the unauthorised activity pending the date for compliance set by the EN.

THE LEGAL CONTEXT

Wellbeing of Future Generations

- Pursuant to section 3 of the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015 (“the 2015 Act”) the Council and the Welsh Ministers are under a duty in the exercise of their functions to take all reasonable steps towards achieving the well-being objectives.

- In relation to the Welsh Ministers’ well-being objectives, the seventh is to “Build a stronger, greener economy as we make maximum progress towards decarbonisation.” Well-being objective nine is to: “Embed our response to the climate and nature emergency in everything we do.”

Planning permission and EIA

- Planning permission is required for the carrying out of any development of land, including mining operations: section 57(1) Town and Country Planning Act 1990 (‘the 1990 Act’).

- A planning authority must not grant planning permission or subsequent consent for EIA development unless an EIA has been carried out in respect of that development: Town and Country (Environmental Impact Assessment) Regulations 2017 (‘the 2017 Regulations’). EIA development includes Schedule 1 development and Schedule 2 development that is likely to have significant effects on the environment. Schedule 1 development includes open-cast mining where the surface area of the site exceeds 25 hectares. Schedule 2 development includes any change to or extension of development of a description listed in Schedule 1.

- Where it appears to a relevant planning authority that proposed development is Schedule 2 development, it must provide a written statement expressing the planning authority’s opinion as to whether the development “is likely to have significant effects on the environment” and is thus EIA development: regs 2 and 8 of the 2017 Regulations. In reaching that opinion, the characteristics of the development must be considered with particular regard to certain factors set out in Schedule 3 of the 2017 Regulations, including pollution.

Enforcement powers

- Part VII of the 1990 Act addresses enforcement of planning control. Section 171A(1) provides that a “breach of planning control” is constituted by:

“(a) carrying out development without the required planning permission; or

(b) failing to comply with any condition or limitation subject to which planning permission has been granted…”.

- Section 171A(2) provides, amongst other things, that the issue of an enforcement notice and the service of a breach of condition notice constitute “enforcement action”.

- Section 172 provides:

“(1) The local planning authority may issue a notice (in this Act referred to as an “enforcement notice”) where it appears to them

(a) that there has been a breach of planning control; and

(b) that it is expedient to issue the notice, having regard to the provisions of the development plan and any other material considerations.”

- Section 182 (as applied to the Welsh Ministers by article 2 and schedule 1 of the National Assembly for Wales (Transfer of Functions) Order 1999) provides:

“(1) If it appears to the Secretary of State to be expedient that an enforcement notice should be issued in respect of any land, he may issue such a notice.

(2)The Secretary of State shall not issue such a notice without consulting the local planning authority.

(3)An enforcement notice issued by the Secretary of State shall have the same effect as a notice issued by the local planning authority.”

- The Planning Encyclopaedia at 182.01 notes that

“[s]trictly, and in contrast to s.172, there are no express tests of it having to appear to the Secretary of State that there has been a breach of planning control and having to have regard to the provisions of the development plan and to any other material considerations. However, there is no good reason to infer that the Secretary of State could lawfully issue an enforcement notice without first applying these tests. They are of course very likely to arise in consultation with the local planning authority in any event.”

- An enforcement notice must give 28 days notice before it takes effect (section 172(3)) and must specify the period at the end of which activities are required to have ceased (section 173(9)). If an appeal is made against the enforcement notice, the notice has no effect until the final determination or withdrawal of the appeal (section 175(4)).

- Where there is non-compliance with an enforcement notice, then: i) the owner of the land is guilty of an offence, as is any person who has control of or an interest in the land who carries on or permits an activity required by the notice to cease (section 179); and ii) the local planning authority may enter the land and take the steps required to be taken by the notice, and recover the reasonable costs of so doing from the person who is owner of the land (section 178(1)).

- Section 171E of the 1990 Act provides for the issue of a temporary stop notice in circumstances where the local planning authority thinks (a) that there has been a breach of planning control in relation to any land, and (b) that it is expedient that the activity (or any part of the activity) which amounts to the breach is stopped immediately. As explained in the explanatory memorandum to the Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act 2004, temporary stop notices are intended to give local planning authorities the means to prevent unauthorised development at an early stage without first having had to issue an enforcement notice. It allows them up to 28 days to decide whether further enforcement action is appropriate and what that action should be, without the breach intensifying by being allowed to continue.

- Section 183 of the 1990 Act provides a planning authority with power to serve a stop notice where it considers it expedient that any activity specified in an enforcement notice should cease before the expiry of the period for compliance with an enforcement notice. The effect of a stop notice is to prohibit the carrying out of the activity. Section 184 of the 1990 Act provides that the notice must specify the date on which it will take effect and that date must not be earlier than three days after the date when the notice is served unless the planning authority considers there are special reasons for specifying an earlier date.

- Section 185 of the 1990 Act (as applied to the Welsh Ministers by article 2 and schedule 1 of the National Assembly for Wales (Transfer of Functions) Order 1999) provides that a stop notice may be served by the Welsh Ministers, after consultation with the local planning authority.

- Section 186 provides that, in certain circumstances, compensation may be payable for loss and damage directly attributable to the prohibition in the notice. However, compensation is not payable, inter alia:

- solely because an appeal against the underlying enforcement notice succeeds on ground (a) in s 174(2) of the 1990 Act e.g. solely because on appeal planning permission is granted; or

- in respect of the prohibition in a stop notice of any activity which, at any time when the notice is in force, constitutes or contributes to a breach of planning control.

- In Huddlestone v Bassetlaw District Council [2019] PTSR at [26] Lindblom LJ highlighted that this provision reflects the thinking of Robert Carnwath QC, in his report of February 1989 ‘Enforcing Planning Control’ that:

“if the Act made clear that compensation will not in any circumstances be payable for a use or operation which is in breach of planning control, there would be less concern at the risks of a notice failing on a technicality, and the use of stop notices in appropriate cases would be encouraged”: para 9.5.”

Relevant case law

Discretion over enforcement

- As a general rule, enforcement authorities enjoy a wide discretion as to the use or non-use of enforcement powers: see R (Easter) v Mid Suffolk DC [2019] EWHC 1574. In R (Community Against Dean Super Quarry Limited) v Cornwall Council [2017] EWHC 74 (Admin), Hickinbottom J. summarised the position as follows:

“25. Where a developer is acting in breach of planning control, the statutory scheme assigns the primary responsibility for deciding whether to take enforcement steps – and, if so, what steps should be taken and when – to the relevant local authority. The statutory language used makes it clear that the authority’s discretion in relation to matters of enforcement – if, what and when – is wide. That is particularly the case in respect of enforcement notices, the power to issue a notice arising only “where it appears to them… that it is expedient to issue the notice”. That is language denoting an especially wide margin of discretion. Any enforcement decision is only challengeable on public law grounds. Because of the wide margin of discretion afforded to authorities, where the assertion is that the decision made is unreasonable or disproportionate, the court will be particularly cautious about intervening. Intervention is likely to be rare. However, circumstances may make it appropriate. In Ardagh Glass, because the four-year period for enforcement was imminently to expire, a failure on the part of the planning authority to take prompt enforcement steps would have meant that the development would achieve immunity. In that case, the court ordered immediate enforcement action to be taken.”

- In Ipswich BC v Fairview Hotels [2022] EWHC 2868 (KB), Holgate J. endorsed the statement of HHJ Mole QC in Ardagh Glass Ltd v Chester City Council [2009] EWHC 745 (Admin) that “expedience” indicates the balancing of the advantages and disadvantages of taking a particular course of action and said the following:

“So, even though the authority may be satisfied that a breach of planning control has occurred, they may consider it not expedient to issue an enforcement notice because on balance the use causes no planning harm at all, or is beneficial, or may cause insufficient harm to justify the taking of any enforcement action. Alternatively, the authority's conclusions on expediency may determine the nature and extent of any enforcement action they decide to take.”

- As such, a decision on the expediency of enforcement action requires an active weighing of the advantages and disadvantages of enforcement. While the enforcement authority will have a wide margin of discretion in that exercise, it must address its mind to the question properly, and must reach a decision that is reasoned and lawful in public law terms.

- In determining whether it is expedient to take enforcement action, an enforcement authority must take into account the development plan and other material considerations. However, there may be circumstances in which it is not only expedient but necessary to take enforcement action prior to a final determination of the planning merits of the unauthorised development. In Ardagh Glass, HHJ David Mole QC quashed the defendant council’s decision that it was not expedient to serve an enforcement notice prior to a decision on planning permission and made a mandatory order requiring the council to issue an enforcement notice requiring the removal of unauthorised buildings. In that case, the developer had built and operated a glass factory without planning permission and without having carried out an EIA. It subsequently made a retrospective application for planning permission accompanied by an EIA to the local planning authority. The claimant and the local planning authority disagreed about the relevant date on which the development would become immune from enforcement action. In any case, the local planning authority was unwilling to issue an enforcement notice while it was considering whether to grant planning permission and said it was “for them to decide whether and when it is expedient to take enforcement action”.

- The judge held at [46] that “it would be a betrayal by the planning authorities of their responsibilities and a disgrace upon the proper planning of this country” for the development to become immune from enforcement action while the local planning authority was considering whether to grant planning permission. He found at [64] that the local planning authority had erred in concluding it was not expedient to issue an enforcement notice. Separately, the judge concluded at [110] that to permit the development to achieve immunity would amount to a breach of the UK’s obligations under the EIA Directive.

- On appeal in the Court of Appeal [2011] PTSR, Sullivan LJ at [22] rejected the submission that the Court should also have made a mandatory order for the service of a stop notice. An enforcement notice was, he concluded, sufficient to ensure the removal of the unauthorised EIA development if retrospective planning permission was not granted.

- In An Application by Friends of the Earth Limited for Judicial Review [2017] NICA 41, the courts of Northern Ireland addressed a different situation where the service of a stop notice was arguably required. The case related to unauthorised extraction of sand from a freshwater lough which was considered likely to have significant effects on the environment. Under the applicable regime in Northern Ireland, the Department of the Environment served an enforcement notice on the landowner and those responsible for the extraction to cease the dredging of the lough. The enforcement notice identified specific concerns relating to compliance with the EIA Directive and the Habitats Directive. The landowner and those responsible for the extraction appealed against the enforcement notice, with the effect that it had no effect pending the final determination or withdrawal of the appeal, and the sand extraction continued. The Minister decided not to issue a stop notice because he considered it disproportionate “where there is no evidence that dredging… is having any impact on the environmental features of the lough”. Friends of the Earth challenged that decision by way of judicial review, alleging that the failure to issue a stop notice was an unlawful exercise of the Minister’s discretion.

- At first instance, Maguire J. dismissed the claim, relying on the judgment of Sullivan LJ in Ardagh Glass. On appeal from the first instance judgment of Maguire J, the Court of Appeal in Northern Ireland distinguished Ardagh Glass as follows:

“[30] Maguire J referred to paragraph [22] of Ardagh Glass Ltd as being in point in the present cases. There was an Enforcement Notice already in existence, the issue was whether a Stop Notice had to be served and there was also an appeal against the Enforcement Notice. It was stated that Sullivan LJ plainly viewed his conclusion on the point as not inconsistent with EU law and Maguire J stated that he was inclined to follow that view.

[31] Maguire J rejected the proposed distinction of the decision in Ardagh Glass Ltd based on the possibility of rectifying the damage in Ardagh by requiring the building to be removed if planning permission was not granted, whereas in the present case it was not possible to return extracted sand.

[32] This Court is of the opinion that there is a distinction to be made between Ardagh Glass Ltd and the present case and that it bears on the application of the principles to be applied. In Ardagh Glass Ltd it was found that the issue of an Enforcement Notice was sufficient to ensure the removal of the unauthorised development if retrospective planning permission was not granted. While the workings might continue in the meantime, it was recognised that ultimately, if necessary, the unauthorised development, in the form of the factory structure, could be removed. However the present case is different in character. There is no such structure to be removed in the event that planning permission is ultimately refused. The unauthorised development is the excavation which cannot be reinstated. Of course, as in Ardagh Glass Ltd, there will also be the ongoing operations at the site but the focus is on the structure rather than the workings. In the present case the issue of the Enforcement Notice will not be sufficient to ensure the removal of the unauthorised development in the form of the excavation between now and the refusal of planning permission. The material extracted is irreplaceable. Therefore the basis on which no Stop Notice was issued in Ardagh Glass Ltd does not apply in the present case.”

- The Court reasoned that the precautionary principle applied to the question of whether to issue the stop notice and operated on the basis that there should be no planning permission until it was established that there was no unacceptable impact on the environment: at [34] “[t]he proper approach is to proceed on the basis that there is an absence of evidence that the operations are not having an unacceptable impact on the environment” (emphasis in the original). Accordingly, the Court held that the decision to issue a stop notice was one over which the decision maker had discretion but – in the circumstances of that case – concluded that the discretion had been exercised unlawfully and quashed the decision.

THE POLICY CONTEXT

Development Management Policy

- Paragraph 14.2.2 of the Development Management Manual provides that the carrying out of development without first obtaining permission should be discouraged, and that “wilful disregard for the need for planning permission is not to be condoned.” Paragraph 14.7.1 provides:

“Where an LPA considers that an unauthorised development is causing unacceptable harm to public amenity, and there is little likelihood of the matter being resolved through negotiations or voluntarily, they should take vigorous enforcement action to remedy the breach urgently, or prevent further serious harm to public amenity.”

- In a letter dated 17 October 2018, the Chief Planner, Planning Directorate, Welsh Government emphasised the importance of timely use of enforcement powers (‘the Chief Planner’s 2018 Letter’) and highlighted the serious risks posed to trust and confidence in the planning system of failures to take timely enforcement action. It notes:

“An effective development management system requires proportionate and timely enforcement action to maintain public confidence in the planning system but also to prevent development that would undermine the delivery of development plan objectives.

The Welsh Government enforcement review concluded, whilst the system is fundamentally sound, it can struggle to secure prompt, meaningful action against breaches of planning control. The system can also be confusing and frustrating for complainants, particularly as informed offenders can intentionally delay enforcement action by exploiting loopholes in the existing process…

Section 3.6 of Planning Policy Wales is clear; enforcement action needs to be effective and timely. This means that Local Planning Authorities should look at all means available to them to achieve the desired result. In all cases there should be dialogue with the owner or occupier of land, which could result in an accommodation which means enforcement action is unnecessary.

…Section 14.2 of the Development Management Manual… deals with how this policy should be implemented. Paragraph 14.2.5 is particularly useful in that it explains how the dialogue with the owner or occupier is one aspect of dealing with an enforcement case but it should not be a source of delay or indecision.”

Coal policy in Wales

- Welsh Government Policy on the extraction and use of coal is clear: “the presumption will always be against coal extraction.” This includes the extension of existing coaling operations. The Coal Policy Statement provides:

“The opening of new coal mines or the extension of existing coaling operations in Wales would add to the global supply of coal having a significant effect on Wales’ and the UK’s legally binding carbon budgets as well as international efforts to limit the impact of climate change. Therefore, Welsh Ministers do not intend to authorise new Coal Authority mining operation licences or variations to existing licences. Coal licences may be needed in wholly exceptional circumstances and each application will be decided on its own merits, but the presumption will always be against coal extraction.

Whilst coal will continue to be used in some industrial processes and non-energy uses in the short to medium term, adding to the global supply of coal will prolong our dependency on coal and make achieving our decarbonisation targets increasingly difficult. For this reason, there is no clear case for expanding the supply of coal from within the UK. In the context of the climate emergency, and in accordance with our Low Carbon Delivery Plan, our challenge to the industries reliant on coal is to work with the Welsh Government to reduce their reliance on fossil fuels and make a positive contribution to decarbonisation.

Planning Policy Wales (PPW 11) already provides a strong presumption against coaling, with the exception of wholly exceptional circumstances, and Local Planning Authorities are required to consider this policy in the decisions they make.”

- Planning Policy Wales (“PPW”) provides that proposals for opencast mines should not be permitted:

“5.10.14 Proposals for opencast, deep-mine development or colliery spoil disposal should not be permitted. Should, in wholly exceptional circumstances, proposals be put forward they would clearly need to demonstrate why they are needed in the context of climate change emissions reductions targets and for reasons of national energy security.”

- PPW acknowledges that exceptionally proposals for industrial uses for coal might come forward and would need to be considered individually against, inter alia, the policies in MTAN 2: Coal.

ANALYSIS

- Planning permission for the extraction of coal on the Site expired on 6 September 2022. Any coaling beyond that date is in breach of planning control. The Council’s refusal of the s 73 application on 26 April 2023 demonstrates that the unauthorised development is unacceptable in planning terms.

- Notwithstanding the absence of planning permission and the service of the EN, there is compelling evidence that coaling continues on the Site. It seems likely that coaling will continue for the duration of any appeal against the EN. Accordingly, in the absence of a stop notice, it is likely that MSWL will have enjoyed the full benefits of the 18 month extension to the Planning Permission it sought, with none of the attendant mitigations or obligations that might have been imposed through a s 73 permission.[5]

- It appears to us that MSWL has demonstrated a “wilful disregard for the need for planning permission" which the Development Management Manual says should not be condoned. MSWL has adopted a deliberate strategy to use the planning system to its advantage to ensure it can continue to extract coal for as long as possible, notwithstanding the breach of planning control. The Council and the Welsh Ministers have enabled that strategy by failing to discharge their enforcement functions effectively. This is exactly the situation the Chief Planner sought to discourage through his 2018 letter and the exact opposite of the “vigorous enforcement action to remedy the breach urgently” encouraged by the Development Management Manual.

- If the breach in this case related to the erection of an unauthorised structure that could be removed at the conclusion of a prolonged enforcement process, that would be one thing. But this case relates to the ongoing extraction of coal. As in the Friends of the Earth case, the ongoing breach of planning control can never be remedied: the coal cannot be put back into the ground; the greenhouse gas emissions attributable to the development can never be un-emitted.

- We consider that the factors in favour of urgent enforcement action in this case are even more compelling than in Friends of the Earth. By contrast to that case, planning permission has now been refused and the planning harm of the unauthorised development confirmed. The effect of the Council’s and Welsh Ministers’ current enforcement approach is to allow an extensive period of coaling, without permission and without the constraints of planning conditions or obligations, when the activity is contrary to national and local planning policy and causes demonstrable planning harm. That approach undermines public confidence and brings the planning system into disrepute.

- In the 1989 Report that formed the basis for the enforcement regime introduced in Part VII of the 1990 Act, Robert Carnwath QC suggested three primary objectives for an effective enforcement system:[6]

- bringing an offending activity within planning control;

- remedying or mitigating its undesirable effects; and

- punishment or deterrence.

- The approach of the Council and Welsh Ministers in this case has failed to achieve any of those objectives.

The unauthorised development is likely to be EIA development

- We consider the unauthorised development is likely to be EIA development because it is Schedule 2 development which is likely to have significant effects on the environment. It has not, however, been subjected to proper scrutiny under the EIA Regulations.

- Although the Council’s First and Second Screening Opinions concluded the proposed nine- and 18-month extensions were not EIA development, we consider those screening opinions were legally flawed. Both concluded that all the impacts of the proposed extensions to the Planning Permission had been assessed in 2005 when it was first granted. That was wrong. In particular, none of the climate change effects of the development had ever been assessed. That is because the requirements of EIA, and the policy context, have evolved since 2005.

- It is not mandatory, in all cases, to assess the climate change effects of development as part of a screening opinion. However, in the context of national planning policy that imposes a strong presumption against coal development on account of its contribution to climate change, we consider that local planning authorities in Wales are required to address the climate change effects of proposed coal development at the screening stage. Those effects would necessarily have included the ongoing operational emissions of the mine, including methane emissions. They may also have included the downstream emissions of burning more than half a million tonnes of extracted coal. As the Court of Appeal confirmed in Finch v Surrey County Council [2022] EWCA Civ 187 at [63], whether the downstream impacts of scope 3 greenhouse gas emissions were “indirect effects” of the development that needed to be assessed was a matter of fact and judgement for the local planning authority. In the context of national planning policy that includes a strong presumption against coal development on account of its downstream effects on climate change, it is arguable that, in Wales, those effects must be assessed in the EIA process as a matter of policy; but it is clear that a local planning authority must at least consider whether to include those downstream effects in its consideration of the likely significant effects of coal development.

- In this case, the Council failed to address the climate change effects of the development at all in its Screening Opinions because it erroneously thought that all the effects of development had been considered and approved prior to granting the Planning Permission.

- Operational emissions caused by an 18-month extension are likely to be in the region of 870,000 tonnes CO2e.[7] The downstream emissions from burning more than half a million tonnes of coal are in the region of 1.2 million tonnes CO2.[8] 2 million tonnes CO2e (a conservative estimate given the figures 870,000 + 1.2 million tonnes CO2) is the greenhouse gas equivalent of burning over 850 million litres of petrol.[9] Put another way, 18 months of mining at this one mine would generate the equivalent of the annual greenhouse gas emissions attributable to about 155,000 residents of Wales.[10]

- While significance for the purposes of EIA is a matter of judgement, and there is no strict algorithm for assessing the significance of greenhouse gas emissions,[11] we consider it likely that the Council would have concluded that that scale of greenhouse gas emissions was likely to have significant effects on the environment.

- In any case, the First and Second Screening Opinions were premised on the Council’s 2005 conclusion that the impacts of development were acceptable “subject to mitigation and limitations provided by planning conditions”. The unauthorised development that is currently taking place on the Site is not subject to any mitigation or limitation provided by planning conditions or otherwise. It is wholly unauthorised and therefore wholly unconstrained. As a result, the First and Second Screening Opinions do not answer the question of whether the unauthorised development is EIA development. For all these reasons, we consider that the unauthorised development is likely to be, or at least arguably is, EIA development.

The Council’s failure to consider enforcement action prior to its decision on planning permission was arguably unlawful

- Between 6 September 2022 and January 2023, the Council appears to have been under the misapprehension – apparently in reliance on information provided by MSWL – that there was no breach of planning control at the Site because active coaling had ceased on 6 September 2022. Whether that misapprehension was reasonable is unclear: local residents had informed the Council as early as 12 September 2023 that unauthorised coaling continued on the Site. In any case, since 30 January 2023 at the latest, the Council knew or ought to have known that:

- There had been a persistent breach of planning control at the Site because active coaling had continued without any significant pause since 6 September 2022.

- That breach of planning control was serious because it involved an activity that is prima facie contrary to the Welsh Government’s strong presumption against coal development.

- That strong presumption existed because of the significant effect of new or extended coal development on Wales’s and the UK’s legally binding carbon budgets as well as international efforts to limit the impact of climate change.

Notwithstanding this knowledge, the Council adopted the inflexible position that – because a planning application was pending for the activity – it would first consider whether it would grant planning permission before considering enforcement. It identified 26 April 2023 as the date on which the Planning Application would be considered and determined that enforcement action would only be considered after that date. We consider that approach was arguably unlawful because it amounted to the fettering of a statutory discretion and/or because it was irrational in the circumstances.

- A local planning authority’s enforcement powers are separate from its powers to grant or refuse planning permission. It is an unlawful fettering of discretion to adopt an inflexible approach always to defer a decision on enforcement until after an extant planning permission is determined: see British Oxygen Co Ltd v Minister of Technology [1971] AC 610 at 625D per Lord Reid.

- Where a planning application is pending for development that is clearly in breach of planning control, it may not normally be expedient to take enforcement action until that application has been determined. However, there will be circumstances, such as those in the Ardagh Glass and Friends of the Earth cases where enforcement action is required pending the determination of a planning application.

- We consider that the underlying rationale in the Ardagh Glass and Friends of the Earth cases is that enforcement authorities must not, through their inaction pending the determination of a planning application for unauthorised development or an appeal against an enforcement notice, deprive themselves of the ability to take effective enforcement action should the development be found to be unacceptable in planning terms. In Ardagh Glass, this required the service of an enforcement notice before the date on which the development arguably became immune from enforcement. In Friends of the Earth, this required consideration of a stop notice to “hold the ring” and prevent irremediable harm to the environment pending the outcome of an appeal against an enforcement notice. Where the development at issue is likely EIA development, this principle takes on greater force.

- In this case, the Council’s failure to consider exercising its enforcement function prior to determining the Planning Application was arguably an unlawful fettering of discretion and/or irrational on account of the fact that the following circumstances demanded that enforcement be considered prior to the end of April 2023:

- The unauthorised activity was likely EIA development that had not been subject to EIA.

- The unauthorised activity was prima facie contrary to an important element of Welsh Government policy, namely the strong presumption against coal extraction.

- Delay in considering enforcement until after 26 April 2023 would have the de facto effect of granting (essentially) all the benefits of the Planning Application, with none of the mitigations that might ordinarily be imposed through planning conditions or obligations. Even if an enforcement notice were served on 27 April 2023, it could not take effect until 25 May 2023, some 12 days short of the end of the nine-month period for which planning permission was initially sought.

- As in the Friends of the Earth case, the breach of planning control could not be remedied: the coal could not be put back in the ground, the operational and downstream emissions could not be un-emitted.

- The situation was of MSWL’s making. It was open to MSWL to make an application for an extension to its existing Planning Permission well in advance of its expiry but instead MSWL chose to submit the application only 5 days short of expiry in an apparent attempt to “game the system”. Moreover, MSWL appears not to have been candid with the Council about its intention and subsequent action to continue active coaling in breach of planning control.

- Without prompt service of an enforcement notice, there would be no consequence for MSWL’s unauthorised development and no deterrent effect for other operators considering similar breaches of planning control:

- because the Council could not, at a future date, reasonably require it to “put back” the coal extracted without permission, there was no risk of significant future expenditure for MSWL in returning the land to its former state (beyond what is already required by the restoration plan which forms part of the Planning Permission);

- without service of an enforcement notice, MSWL could enjoy the profits of its unauthorised coaling without the risk of having the gross receipts confiscated under the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (see R v Luigi del Basso [2011] 1 Cr. App. R. (S.) 41).

- For these reasons, a delay in consideration of enforcement until after 26 April 2023 would clearly undermine public confidence, bring the planning system into disrepute, and set a harmful precedent that would fail to deter, and might encourage, other developers of land to act in a similar manner.

- In suggesting that the approach adopted by the Council was arguably irrational we do not say there was only one rational approach available to the Council. There were a range of options available to the Council to enable it to address the breach of planning control pending the determination of the Planning Application. It could have:

- investigated reports of a breach of planning control when first drawn to its attention in September 2022;

- engaged in dialogue with MSWL to seek its agreement to stop coaling without the need for enforcement action;

- issued a temporary stop notice to give time to consider appropriate enforcement action and/or to expedite determination of the Planning Application;

- served an enforcement notice;

- expedited the consideration of the Planning Application.

- To have done none of these things but instead simply deferred consideration of all enforcement matters until after the Committee’s consideration of the Planning Application on 26 April 2023 – almost eight months into the nine-month period for which planning permission was initially sought – was arguably an unlawful fettering of discretion and/or Wednesbury

The Council’s failure to serve a stop notice is arguably unlawful

- MSWL has demonstrated a willingness to game the planning system and operate in breach of planning control where there are no consequences for doing so. Should the EN take effect on 27 June 2023, there will be criminal consequences for non-compliance from 25 July 2023. However, if MSWL appeals the EN (which seems likely), there will be no consequences for that continuing breach of planning control until the final determination of the appeal.

- In the circumstances, the clear and obvious solution is for the Council to serve a stop notice before 27 June 2023 or as soon as possible after MSWL appeals the EN.[12] We consider it so clear and obvious that a decision not to do so would arguably be unlawful.

- The parallels between this case and the Friends of the Earth case are clear. Each day of dredging in that case / coaling in this case causes irremediable harm. As the Court of Appeal in Northern Ireland noted:

“the unauthorised development is the excavation which cannot be reinstated… the issue of the Enforcement Notice will not be sufficient to ensure the removal of the unauthorised development in the form of the excavation between now and the refusal of planning permission. The material extracted is irreplaceable.”

- In circumstances where MSWL appeals the EN, the failure to serve a stop notice will have the de facto effect of granting MSWL all the benefits of the planning permission it was refused, with none of the mitigations that would otherwise have been imposed on that permission, and permitting the harm which underpinned the Council’s decision to refuse planning permission.

- In the exercise of its statutory functions, the Council must address the question of whether it is expedient to serve a stop notice. In doing so it must balance the advantages and disadvantages of doing so. In the circumstances as set out above, it is very difficult to see how, rationally, the Council could conclude that the disadvantages of serving a notice outweigh the advantages. Indeed, it is not clear to us that there are any disadvantages to weigh in the balance.[13]

- There is no realistic prospect of MSWL recovering compensation in respect of the stop notice. As the Court of Appeal highlighted in Huddlestone, section 186 of the 1990 Act does not permit compensation in respect of any activity which constitutes a breach of planning control. It is drafted in this way precisely to encourage enforcement authorities to serve stop notices in appropriate cases, like this one.

The Welsh Ministers failure to consider issuing an enforcement notice before the Council took its own decision was arguably unlawful

- Under section 182 of the 1990 Act, the Welsh Ministers have a power to issue an enforcement notice if, after consultation with the local planning authority, they consider it expedient to do so. The position of the Welsh Ministers in correspondence in this case was that they would only consider exercising their discretion to issue a notice if and after the Council had decided not to do so.

- That position was arguably unlawful because it amounted to a fettering of an independent statutory discretion. While the Welsh Ministers must consult with the Council before issuing an enforcement notice, their discretion is not constrained by the Council’s consideration of enforcement. In (Hammerton) v London Underground Ltd [2003] J.P.L. 984 Ouseley J. said at [139]:

“[a] lawful positive decision to the effect that it would not be expedient for the purposes of section 172 to issue an enforcement notice would eventually lead to the development in breach becoming lawful with the passage of time but of itself would not stop the permission lapsing. A lawful positive decision by a local authority cannot without more preclude the exercise by the Secretary of State of his default powers under section 182”.

- Thus, it should be noted that: (i) a decision by the local planning authority that enforcement action is not expedient cannot preclude the Secretary of State taking a different view and exercising the powers available under section 182; and (ii) the powers conferred by section 182 are referred to as “default powers”. In relation to this in v Hereford and Worcester CC Ex p. Smith (Tommy) [1993] 4 WLUK 79 [1994] C.O.D. 129 it is referred to as a “reserve power”.

- These phrases (“default powers” and “reserve power”) indicate that while it may be a lawful approach for the Welsh Ministers normally to defer to a local planning authority in the first instance on enforcement matters, the Welsh Ministers must not close their mind to the possibility, in an appropriate case, of taking enforcement action where a local planning authority is failing to “secure prompt, meaningful action against breaches of planning control” as required by policy. We consider this to be exactly such a case. In that regard, we refer to the factors at paragraph 84(a) and (c)-(g) above and note in addition that:

- On 18 October 2023, the Welsh Ministers issued a holding direction in relation to the Planning Application. That holding direction was the exercise of a statutory function by the Welsh Ministers to ensure they would have meaningful control over whether a nine-month extension of coaling at the Site should be permitted.

- The Council’s indication that it would not consider enforcement action until after 26 April 2023 had the de facto effect of depriving the Welsh Ministers of any meaningful call-in function and any meaningful enforcement function. If the Welsh Ministers were to call in the application only after the Council resolved that it would grant planning permission, that call-in would be a pantomime: MSWL would already have enjoyed the nine months of coaling for which it sought permission. Similarly, if the Welsh Ministers were to consider enforcement only after the Council had done so, it would be doing so after the nine month period for which planning permission was sought.

- Welsh Ministers must, when exercising their functions, take all reasonable steps towards, inter alia, making maximum progress towards decarbonisation and embedding their response to the climate and nature emergency in everything they do.

- In those circumstances, the Welsh Ministers were arguably required to at least consider issuing an enforcement notice prior to the Council’s decision on enforcement. Their failure to do so was arguably an unlawful fettering of discretion and/or irrational and/or a breach of s 3 of the 2015 Act. It had the effect of denuding the Welsh Ministers of any effective power of call-in and any effective power of enforcement in relation to a clear and serious breach of planning control which was, as a matter of policy, causing harm to decarbonisation efforts.

The Welsh Ministers must urgently consult with the Council and consider, independently, whether to serve a stop notice.

- Under section 185 of the 1990 Act, the Welsh Ministers have an independent statutory power to serve a stop notice if, after consultation with the local planning authority, they consider it expedient to do so. It is not a condition for the exercise of that power that the local planning authority has already considered and rejected the expediency of serving a stop notice.

- As set out above, the failure to serve a stop notice may have the de facto effect of granting MSWL all the benefits of the 18-month extension to the Planning Permission it was refused, with none of the mitigations that would otherwise have been imposed on that permission, and permitting the harm which underpinned the Council’s decision to refuse planning permission.

- The ongoing serious breach of planning control at the Site, and the Council’s ongoing failure to take prompt and effective enforcement action, is squarely before the Welsh Ministers. As a result, we consider their statutory enforcement powers are engaged and they are under a legal obligation to consult with the Council as a matter of urgency to consider what steps will be taken, and by whom, to ensure that coaling is not permitted to continue for an extended period in breach of planning control for the duration of any appeal against the EN.

- Unless the Council indicates, through consultation, an intention to serve a stop notice itself, the Welsh Ministers must consider whether it is expedient to do so themselves. They must balance the advantages and disadvantages of serving a stop notice. In the circumstances as set out above, it is very difficult to see how, rationally, the Welsh Ministers could conclude that the disadvantages of serving a notice outweigh the advantages. Indeed, it is not clear to us that there are any disadvantages to weigh.

NEXT STEPS

- We advise Coal Action Network to press the Council and the Welsh Ministers to serve a stop notice as a matter of urgency and/or to explain what other mechanism they intend to use to ensure that unauthorised coaling is brought to an end immediately. Should the Council and Welsh Ministers refuse to do so, we will advise on the merits of judicial review, including interim injunctive relief. In the abstract, and without knowledge of any special circumstances that might be revealed in correspondence, we consider that such a claim would have reasonable prospects of success.

- As for the Council’s and Welsh Ministers’ eight-and-a-half month delay in issuing an enforcement notice, we doubt there is much to be gained through litigation at this stage. However, we advise Coal Action Network to consider referring the matter to the Public Services Ombudsman for Wales. In our opinion, the collective failure to take prompt, meaningful action against the breach of planning control constitutes maladministration for the purposes of the Public Services Ombudsman (Wales) Act 2019. The Ombudsman has previously investigated complaints relating to failures to take effective enforcement action and has made recommendations for compensation.

21 June 2023

JAMES MAURICI KC

Landmark Chambers

TOBY FISHER

Matrix Chambers

[1] For the references and calculations behind these figures, see fns 7 – 11 below.

[2] See R. (Holding & Barnes Plc) v Secretary of State for the Environment, Transport and the Regions [2003] 2 A.C. 29569 per Lord Hoffmann at [69] “[i]n a democratic country, decisions as to what the general interest requires are made by democratically elected bodies or persons accountable to them … sometimes one cannot formulate general rules and the question of what the general interest requires has to be determined on a case by case basis. Town and country planning or road construction, in which every decision is in some respects different, are archetypal examples. In such cases Parliament may delegate the decision-making power to local democratically elected bodies or to ministers of the Crown responsible to Parliament. In that way the democratic principle is preserved.”

[3] Application P/22/0237

[4] See https://shorturl.at/pAN19.

[5] If the Council had concluded that “wholly exceptional circumstances” had been made out, it might reasonably have been expected to require the mitigation of the climate change effects of the extension by, for example, requiring the developer to offset its emissions.

[6] Robert Carnwath QC, Enforcing Planning Control, HMSO February 1989.

[7] MSWL reported its 2021 emissions as 930,533 tonnes CO2e, excluding methane emissions. (2021 Annual Accounts p 4, Companies House) Coal Authority quarterly reports indicate that total production in 2021 was 602,128; operational (non-methane) emissions were thus reported to be 1.55 tonnes CO2e per tonne of coal mined. Assuming a rate of 1.5 tonnes CO2e per tonne of coal for the 500,000 tonnes coal estimated to be mined during an 18-month period leads to an estimate of approximately 750,000 tonnes CO2e. Methane emissions from the Ffos-y-fran mine has been estimated to be 2,077 tonnes over a 9-month extension by Global Energy Monitor using methodology from Kholod et al, 256 Journal of Cleaner Production (2020), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120489. This equates to 4,154 tonnes over 18 months. Using a conservative estimate of 30 for the global warming potential of methane to convert to carbon dioxide equivalent (see https://www.iea.org/reports/methane-tracker-2021/methane-and-climate-change) this equates to a further 124,620 tonnes CO2e. Or, in all, roughly 870,000 tonnes CO2e.

[8] The 2023 BEIS conversion factor for industrial coal is used (this being a conservative assumption, as the domestic coal conversion factor would produce a higher figure). 500,000 tonnes of coal x 2.39648 BEIS figure for tonnes of CO2e = 1.198 million tonnes CO2 equivalent.

[9] 2023 BEIS conversion factor for Petrol is 2.35 Kg CO2e per Litre. 851M Litres x 2.35 = 2 billion Kg or 2 Million tonnes.

[10] Per capita annual GHG emissions in Wales are 8.6 tonnes CO2e per person. See https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/uk-local-authority-and-regional-greenhouse-gas-emissions-national-statistics-2005-to-2020, statistical summary (30 June 2022). Over an 18-month period this equates to 12.9 tonnes CO2e per person in Wales (8.6x1.5). 2 million/12.9 = 155,000.

[11] See the Institute of Environmental Management & Assessment (IEMA) Guide: Assessing Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Evaluating their Significance, Second Edition, February 2022.

[12] Section 183(3) of the 1990 Act provides that a stop notice may not be served where the related enforcement notice has taken effect. However, where an appeal against the enforcement notice is made (which must be done before the enforcement notice takes effect), section 175(4) suspends the effect of the enforcement notice until the appeal is finally determined or withdrawn. Accordingly, if there is an appeal against the EN, the Council may serve a stop notice at any time during the currency of the enforcement appeal. For reasons we have explained, however, we consider that a stop notice should be served urgently without waiting for an appeal to be made.

[13] We have considered whether the Council might judge that permitting the continued operation in breach of planning control might be desirable to enable the operator to make profits to plug a shortfall in its available capital for site restoration. We consider this would be an irrelevant consideration in the context of a decision on expediency.