Türkçe için bu web sayfasına bakın.

The small city of Ereğli nestles between tree covered mountains and Turkey’s Black Sea coast. The city is dominated by the Erdemir steelworks. It is one of three blast furnace steelworks in Turkey, using coal to produce steel. Erdemir is a mighty presence in the lives and lungs of the people living nearby.

Local people’s homes sit in an amphitheatre surrounding the vast steelworks, which sends plumes of steam into the air every few minutes that shimmers and obscures apartment blocks across the bay. Investigators from Coal Action Network travelled to Turkey to speak with people currently affected by Turkish coal burning facilities, like the Erdemir steelworks, when it looked possible that a new coal mine would open in Cumbria and supply coal to Turkey, perpetuating the local populations’ air pollution issues. For more information on why Coal Action Network visited Turkey and links to UK coal mining, see this page.

Turkey uses imported coal in its steelworks and power stations, as well as mining domestically.

Turkey is the 8th biggest steel producer globally. In 2023, it produced a massive 33.7 million tonnes of steel and consumed 21.1 million tonnes of scrap metal, according to World Steel Association. 27 of the 30 steelworks in the country produced steel by melting down scrap metal produced in Electric Arc Furnaces (EAF), producing 72% of the country’s steel output. There are three blast furnaces that use coal, converted into coke, in the steel making process, and many of the EAFs use coal to provide heat. This coal is largely imported. Russia supplies 73% of Turkey’s coal imports, and Colombia the bulk of the remainder.

EAFs consume large amounts of electricity. In Turkey, much of this electricity comes from coal through the power grid. One Turkish EAF has its own coal power station. Coal power supplied 35% of Turkey’s electricity in 2022. Turkey both imports and exports large quantities of steel (18 million tonnes and 12.7 million tonnes respectively, in 2023). More than 20 of the EAF steel facilities currently use coal to melt scrap metal. Steel is the country’s third largest export sector.

Turkey is one of the top five importers of Russian coal. Many countries, including the UK, EU member states and USA stopped buying Russian coal, as part of sanctions following the country’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

Vaibhav Raghunandan, from Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA) says, “Turkeyʼs increased reliance on Russian coal (and indeed other fossil fuels) is effectively tying it down to an increasingly volatile supplier who controls their market. The Russian coal sector is a huge source of revenue for the Kremlin and the Energy Ministry had set targets of attaining 25% of the global coal market by 2035. Taxes from coal constitute a significant part of the Federal Budget. Since the invasion, Turkey — A NATO country — has paid EUR 8.2 bn for Russian coal, which effectively finances Russiaʼs invasion of Ukraine.”

Since the invasion Turkey has increased its market share of Russian coal, Turkey’s imports constitute 13% of Russiaʼs total coal exports. In the first three quarters of 2024, Turkey has imported 15.7 million tonnes of Russian coal, making up 49% of Turkey’s total coal imports (valued at EUR 1.66 billion). This is an 82% increase when compared to the same period in the year prior to the invasion.

Additionally, the Russian coal mining industry causes cultural genocide, environmental destruction and air pollution issues, detailed in Coal Action Network and Fern’s report, Slow Death in Siberia.

According to the World Health Organization, air pollution is the largest environmental threat to people’s health across the globe, including in Turkey. There are four main health harming pollutants released in coal consumption from steelworks and power stations: Sulphur dioxide (SO2); particulate matter – PM10 and the smaller PM2.5; nitrogen oxides (NOX) and mercury.

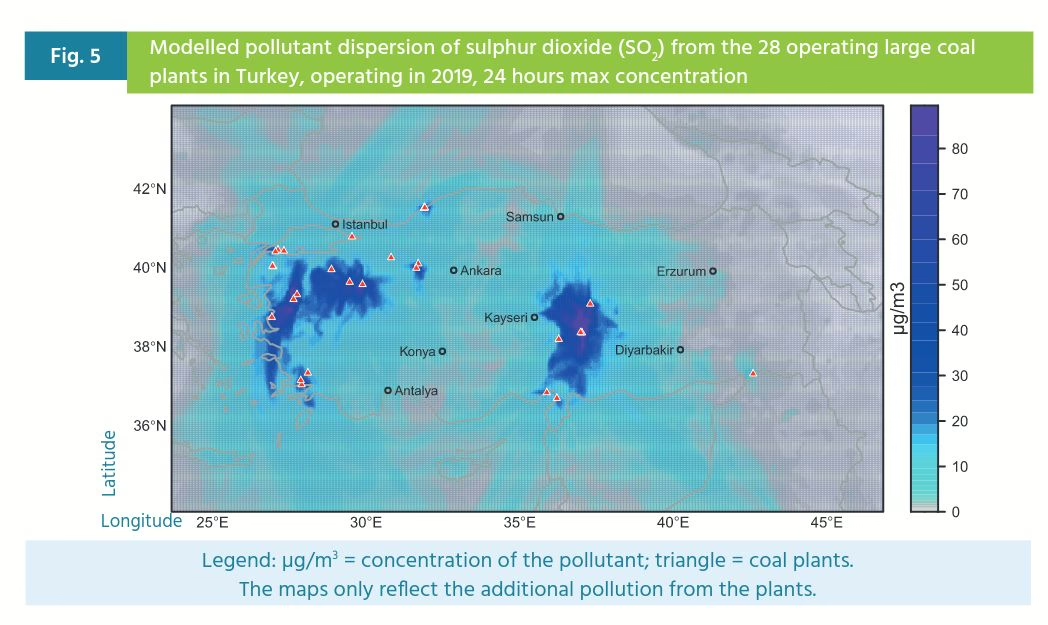

Breathing SO2, which is produced on combustion of high sulphur coal, increases the risk of health conditions – including stroke, heart disease, asthma, lung cancer and death. It is classified as very toxic when inhaled. Even a single exposure to a high concentration can cause a long-lasting condition like asthma. SO2 emissions rose by 14% in Turkey in 2019, one of the few countries in which emissions increased in that year. Coal-based energy production remains the major source of SO2 emissions in Turkey.

Local people in Ereğli, the city surrounding the Erdemir blast furnace steelworks, told Coal Action Network that university studies into their health are normally suppressed by government. However, in a study looking at the incidence of multiple sclerosis (MS) in populations in Ereğli compared to Devrek, which is a rural and clean city located 40 km away from Ereğli, “indicate a more than double MS prevalence rate in the area home to an iron and steel factory [Ereğli] when compared to the rural city [Devrek]. This supports the hypothesis that air pollution may be a possible etiological [Pertaining to, or inquiring into, causes] factor in MS.” Local people take no persuading that the air is contaminated by the steelworks and damaging their health.

Çetin Yılmaz, leader of Black Sea, Ereğli and Alaplı Environmental Volunteers, brought together 15 concerned citizens from Erdemir to talk with Coal Action Network about the impacts they face in the town surrounding the steelworks. They bemoan the scientific studies which show links between the steelworks and the diminishing health of the local population, but which are suppressed by the Government.

Çetin says, “The company [Eren Energy] has caused cancer in many people, it does not recognize the right of their employees to unionize in its facilities; it has fired workers who want to be unionized; it has made Çatalagzı into a breathless state; it has filled fish breeding grounds with ash; it burns 2 million tons of imported coal every year and caused the greatest damage to humans and nature in our region.”

A worker, who has worked at the Erdemir steelworks for 18 years, explained how he got throat cancer, which could be heard affecting his voice when we met him. Local people think 50% of the population’s health is affected by the steelworks. A teacher present recalled how in each of his classes around 10 children will have breathing issues, caused by the poor quality air.

The local political representative told Coal Action Network, “Most people here work in mines or in the steel plant, everyone knows that the air pollution causes cancer and breathing difficulties. The workers aren’t in a position to do anything about it as they have to earn money and would lose their employment, as well as their health.”

OYAK, the company which owns Erdemir and İsdemir blast furnaces, says it will use seven different methods to decarbonise. Its so called Net Zero Roadmap reads more like a list of potential options to reduce emissions and does nothing to resemble an actual plan.

Air pollution and health problems at İsdemir are likely to mimic those at Erdemir. Turkey’s CO2 intensity for the blast furnace steel production exceeds the comparable emissions for steel produced in Europe, the USA, and South Korea.

There have been persistent shortcomings in compliance with environmental, public, and occupational health regulations across the steel production value chain in Turkey.

Sitting at the eastern edge of Europe, Turkey is expected to surpass Germany as Europe's largest coal-fired electricity generator in 2024. Turkey is still opening new coal power stations, such as Hunutlu Thermal Power Plant opened in 2022. Turkey has 34 coal fired power stations, 10 use hard coal and the remainder use lignite, a less energy dense, poorer quality coal that is burnt close to its source. Two of the blast furnaces using coal also have coal power stations providing their electric.

Turkey’s electricity consumption has tripled in the last two decades, which has been underpinned by rapid growth in coal and gas generation.

As well as Ereğli, Coal Action Network visited three coal fired power stations near Muslu, called ZETES III and IV and Çatalağzı. All of the sites are within the district of Zonguldak.

Zonguldak was the only non-metropolitan district included in Turkey-wide weekend curfews for covid-19 reduction measures in 2020. This was due to pre-existing high rates of chronic respiratory diseases caused by poor air quality. According to local officials, it’s estimated that as much as 60% of the population displays some degree of respiratory symptoms, with mortality rates almost doubling between 2010 and 2020. The low air quality is caused by elevated levels of PM2.5 and SO2 pollutants from steelworks, coal mines and hard coal power plants.

The health costs from coal power generation in Turkey alone, are 26.07 - 53.60 billion Turkish Lire (2.86 - 5.88 billion €), which is equivalent to 13 - 27% of Turkey’s annual health expenditure.

Where Turkey significantly deviates from the rest of the EU in relation to steelworks and power stations is in the compliance and enforcement of air quality standards. As a report by Health and Environment Alliance (HEAL) shows, “While EU member states are legally required to report emissions at plant level to a publicly accessible database [...] Turkey does not share power plant or sectoral emission data. Instead, it reports merged data for electricity generation and the heating sector” This obscures the data. Furthermore, Turkey has not signed other important technical agreements to limit, and cooperate on, other pollutants. This includes three protocols on sulphur emissions (The 1985 Helsinki Protocol on the Reduction of Sulphur Emissions, the 1994 Oslo Protocol on Further Reduction of Sulphur Emissions, and the 1999 Gothenburg Protocol to Abate Acidification, Eutrophication and Ground-level ozone.). As HEAL states, “The lack of transparency prevents a rational and informed debate about improving air quality and health in the country.” Local people and ecosystems are left to deal with the consequences.

In the last 20 years, Turkey’s power plants that have been privatised and many do not use filter technology for SOx. They are the major contributor to Turkey’s increasing SOx pollution.

Everyone who spoke to Coal Action Network is worried about the air quality impacts of Turkey’s coal consuming plants. A resident living near three coal power stations on the Black Sea, near Zonguldak, says, “people believe that in some periods the air pollution filters on the plants are not working properly. Habitually, we have 250 days in a year the pollution is higher than the government’s acceptable standards.”

The consistent narrative from the residents overlooking either the steelworks or the coal power stations was one of poor air quality, resulting in higher rates of respiratory illness, cancers of various sorts, and death of plants and vegetation leading to an inability of local people to grow food.

In 2021, Turkey imported 36 million tonnes of coal for its power stations and steelworks, as well as using its domestically mined coal, which is mainly lignite, not used in steel-making. Turkish Coal Enterprises emphasises that the most significant increase in coal imports will come from the demand for electricity generation, and estimates that this trend will continue. Although President Erdoğan says the country will decarbonise by 2053 there is no meaningful road map to bring the blast furnaces into relevant carbon reduction strategies.

Barış Eceçelik from Ekosfer states, “Turkey is one of the few countries in Europe that has not set a date for the phase-out of coal. Last year, for the first time in the history of Turkey, imported coal became the leading energy source in electricity generation. Turkey has significant potential for renewable energy sources, including wind, solar, and biomass. However, the lack of a serious climate target and measures against coal usage has led to air pollution and a high level of energy dependence. It must be acknowledged that imported coal is not a solution to the issues of climate change nor air pollution.”

The pollution issues around the coal power stations do not just affect air quality. They also have a large impact on the Black Sea. The water around the power station is reported to be 4o warmer than elsewhere, as it is used in the power stations cooling processes and then returned warmed to the sea. Local people report seeing a sheen on the water from the heavy metals and other toxins which are released from the power stations. Burning coal high in sulphur increases sulphur dioxide which produces acid rain, and acidifies lakes and streams. Black Sea fishermen say that the power stations are damaging fish spawning grounds and reducing their catch. Food which is sold to Istanbul and Ankara.

Coal is a contested subject in Turkey. While people living close to existing coal facilities want the secure jobs, there are protests against new power stations and a proposed lignite power station was cancelled in 2013, following protests. Mining accidents are fairly common, with 301 killed in just one accident in Soma in 2014.

In the high up mountain village of Kokurdan (official name: Körpeoğlu) a coal ash and waste dump billows clouds of dust onto the dense trees surrounding the settling pool. Ash from the ZETES power stations and the dirt from the air filters are settled in a vast open dump. Although Coal Action Network visited immediately after heavy rain had washed the dust off the vegetation, homes and roads, the waste from ZETES coal power stations normally accumulates in the lungs, homes and crops of these people.

Villagers approached Coal Action Network to ask why we would want to visit their area when the coal facilities cause such contamination. “I hate being from here because of the pollution. When the weather is dry the dust covers everything.” one woman told Coal Action Network, whilst passing on the street in Kokurdan. In this village they are not convinced the damage is worth it because of the jobs. Local people say nothing good about the coal power plants, they just talked about the damaging health effects, adding liver cancer and stomach cancer to the list of illnesses caused by the coal power stations.

The most basic air pollution controls are not being implemented – lorries carrying coal are not even covered to prevent dust spreading along its route, a measure that long ago became standard in the UK. Public roads also run underneath the conveyor belts of ZETES power stations.

Monitors for fine dust particles known as PM10 are apparently not operational around the steelworks. PM2.5, is finer particulate matter that can penetrate the lungs and even enter the bloodstream and cause chronic diseases such as asthma, heart attack and bronchitis. PM2.5 is not monitored at all around Ereğli.

Coal Action Network’s visit to four coal facilities on the Black Sea showed that the human and environmental costs of burning coal are high. The issues of health, local environment and climate change are not being sufficiently addressed, but there is demand for improvement within Turkish communities living close to coal facilities.

In November 2024, the new UK Government announced its intention to legislate a ban of new coal mining licences – which we welcomed. Over a year later, the legislation is yet to be introduced, and the Government is not planning to include all types of extraction…

The UK steel and cement sectors (and to a lesser extent, bricks) are the largest users of coal following the closing down of the UK’s last coal-fired power station in September 2024. Check out our coal dashboard for our most recent coal stats including an industry break-down. We support the UK Government’s commitment to ban…

The steel industry produces 9-11% of the annual CO2 emitted globally, contributing significantly to climate change. In 2024, on average, every tonne of steel produced led to the emission of 2.2 tonnes of CO2e (scope 1, 2, and 3). Globally in 2024, 1,886 million tonnes (Mt) of steel were produced, emitting…

Last month we worked with Members of Parliament from various parties on a Westminster Hall debate about coal tip safety and the prohibition of new coal extraction licences. The debate happened 59 years and one day after the Aberfan tragedy which killed 116 children and 28 adults…

Successful, at-scale, examples already exist of cement works burning 100% fuel alternatives to traditional fossil fuels, including pilot projects using combinations of hydrogen and biomass (UK) and hydrogen and electricity (Sweden). Yet, innovations such as use of hydrogen and kiln electrification are…

Within the borders of the Senedd Caerphilly constituency is the proposed Bedwas coal tips re-mining project. In the lead up to the Senedd by-election, Coal Action Network has carried out a survey of the by-election candidates asking for their views about the re-mining of the Bedwas and other…

In 2019, Bryn Bach Coal Ltd applied to expand its Glan Lash opencast coal mine and extend the amount of time it would continue mining coal for. The proposal would see the coal mine swallowing a nearby ancient woodland, hedgerows, and grassland. The proposal was rejected by Carmarthenshire County Council in 2023…

In November 2024, the UK Government announced its commitment to legislating a ban of new coal mining licences. This was a commitment that Coal Action Network had secured a manifesto commitment from the Government for, along with four other major parties…

Coal Action Network has obtained new legal advice from expert Barristers Estelle Dehon (KC) and Rowan Clapp of Cornerstone Chambers, London. Examining relevant…